I recently completed a Yin Yoga teacher training (ironically enough, after 5 years teaching Yin). One of my takeaways from the training was a reminder of our beliefs around the supposed symmetry and balance of the body. Largely because of how we look, most of us assume that we are bilaterally symmetrical. In other words, that our left and right sides are (or should be) the same. In Yin, and also in much of somatic movement, a major discovery many of us make is that our body, when felt rather than seen, is really not symmetrical at all. It can be surprising, shocking, even horrifying, to notice all the ways in which we are off-kilter, unbalanced, or just plain different from one side to the other. The question becomes: what do we do with this knowledge?

One of the lovely things our teacher trainer kept reminding us was to be aware of, and then accommodate, our internal differences. These could be differences felt from one day to the next, from one body part to another, or from one half of the body to the other. Often if we aren't told or allowed to become aware of these differences, they pass under the radar of our assumption of same-ness. And we act in a blanket way, doing the same thing no matter the current state or response, just because it's easier, or out of habit. Being given permission to sense these internal differences makes room for different responses, which are likely to be more appropriate and more closely matched to our needs.

Sensing asymmetries may at first be somewhat threatening—immediately when I notice something different, I want to understand why. Why doesn't my left hip bend like my right, or why is my right arm so much tighter than my left? The truth is that the specific why is not very important. Maybe it can help to realise that oh, I'm right-handed, so I'm always using my right hand to do things. Or that, oh yeah, I injured my left low back a few years ago, and it seems like my left hip was somehow affected by that experience in a different way to my right. But at the end of the day, what I find most powerful is to overall recognise and accept that none of us are truly symmetrical. We are full of complex combinations of differences, dualities that we can't seem to reconcile, and paradoxes that frighten, challenge, and confuse us.

Another pattern I noticed was, having identified a difference, I would immediately want to fix or change the asymmetry—to 'balance it out'. In my head, 'balance' was some kind of code for neutralising, making things uniform, even, identical, as I unconsciously thought they should be. But is balance equal to sameness? In other words, do two things, in order to be balanced, need to be the same as each other? I am slowly realising that the answer to this is no. No, my left thigh does not need to be as strong/flexible/long/externally or internally rotated as my right, in order for them to be in balance. No, I don't need to do the exact same pose on both sides for the same amount of time, in order to be balanced. No, I don't need to have the same control, ability or range on both sides of my body, in order to be in balance.

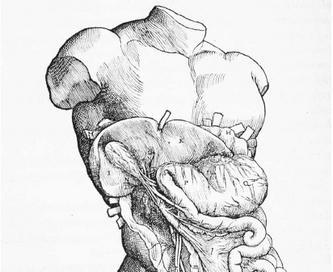

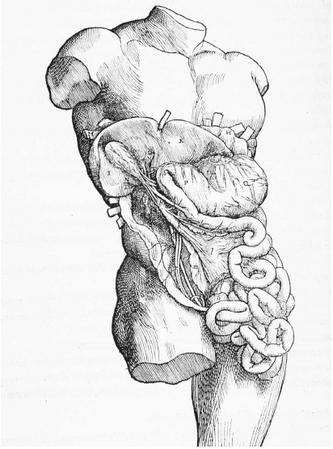

There are a couple of ways I am thinking about this. One is to remember that internally, in quite a literal sense, things are pretty helter-skelter. Our organs sit in twisted, asymmetrical arrangements: the heart is on one side of the body, the left lung shaped and sized differently to the right to accommodate the heart, and the visceral organs on the right and left halves of the belly are often completely different in form, function and arrangement. But somehow, we make this work. In fact, you could say that it is part of how we function to be asymmetrically structured. There is nothing pathological about this, nothing wrong that then has to be fixed, changed, transformed. So why don't we apply the same logic to the rest of the body: arms and legs, muscles and bones?

The second idea that has helped me make sense of this is to remember that our bodies are physical remnants, artefacts of the lives we have led. Everything we have ever done, felt, experienced, is stored somewhere in the body. Handed-ness is an easy example of this. Most of us are not ambidextrous, so one of our hands and arms will be called upon to fulfill certain functions in life, while the other performs a supporting role somewhere in the background. Over time, this will cause differences in the ability and experience of the two hands. Similarly, if our work or long-term activities involve certain parts of the body and not others, those parts will feel and be different to others. Think: sportspeople, dancers, people who labour manually (although note that even people who are sedentary are still using their body in specific ways, but we won't go into that here). If we have ever been ill or injured, those experiences leave a residue in the body that doesn't get magically wiped away when we heal. The body adapts to such experiences—both long-term use and acute illnesses or accidents—by changing internally, shifting its landscape to accommodate what we are going through. So asymmetry is a sign of our body's adaptation response to the experiences of our life. Or, we could say, it is our history, written in the tissues of our body.

Thus far we have seen that (1) asymmetry is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be accommodated; and (2) balance does not equal symmetry. Now the question remains: what does it mean to be balanced? This is probably a very individual inquiry and experience, to be determined by each of us based on how we feel and think about balance. My first steps have been to really examine why I want sameness, identity, so much. Some of this probably goes back to my experience as a ballet dancer; external symmetry being a prized element of this form. Some of it may also have come from the yoga world, from a misunderstanding, or lack of exploration, of what is being referred to by the word 'balance' in a yoga practice and philosophy. I don't think it's a reasonable (or even achievable) goal to 'find balance' by getting rid of all the asymmetries in our physical experience. Even if it were possible, it sounds like it would lead to a kind of bland, undifferentiated flatness that doesn't do justice to our inherent, kaleidoscopic complexity, or our unique, individual history.

As I mentioned, sometimes we get taken over by a kind of instinctive, and rather baseless fear that something is wrong if things aren't the same inside—and this I notice in students too. Undoubtedly it can be unsettling to realise that our inside experience doesn't match our outside ideas. But part of growth, and dare I say, maturity, is to recognise these asymmetries between inner areas, as well as more broadly between our internal and external experience. And then to learn to hold both ends of the duality—the paradoxes in us—without needing to change them. It is a wonderful gift that accommodates the mysterious off-kilter-ness of our reality, instead of pushing for an easy, comfortable, symmetrical ideal. In my experience, this leads to a great softening towards ourselves, a sense of being okay with how we are in this moment, and how we've been for so much of our life. And potentially, having accepted where we are, we are better placed to make choices that will lead us on towards integration and synthesis: becoming whole beings made of distinct, asymmetrical, yet balanced parts.