For my mum, who was born and raised in Delhi, and is my living link to the city.

Hello everyone. I interrupt my series of posts on stress to send you a postcard from my trip to Delhi. I hope you enjoy the following photos and the atmosphere of the historic city, as I did. Please note that because of all the images, this post may be too long for your email—click on the title above to read it in full in your browser.

On the plane, I read William Dalrymple’s captivating book A City of Djinns. If you like travel literature, or are interested in the history of Delhi, I highly recommend it. It’s the kind of story I wish I could tell. But I can neither confirm nor deny meeting any djinns while I was there.

Road Trip to a Pilgrimage Town

While I spent most of my time in Delhi, I made a brief road trip to Vrindavan, a sacred town south-east of the city. It was full of pilgrims doing parikrama, or circumambulation. So full that there was a human traffic jam the day we left. There are temples everywhere, on every street and corner, between shops and houses, wherever you look.1

And many, many cows. The people of Vrindavan believe that you get better milk when cows are left to roam freely, so they let them out every morning to wander around. Many people feed them chappatis, and/or scraps from the kitchen. (The first time I stepped out of my grandmother’s house, a white cow ambled up and started eating banana peels off the scrap pile outside the house.) In the evening the cows will return home on their own.

Pleasure Gardens of Delhi

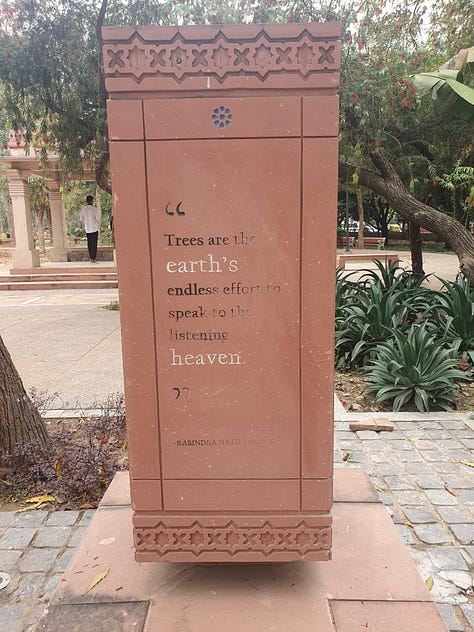

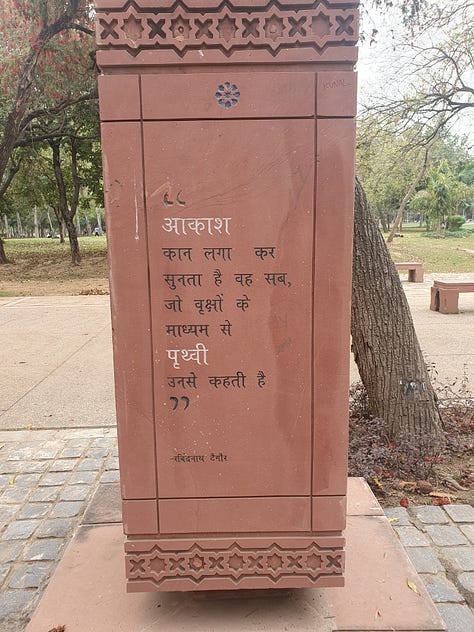

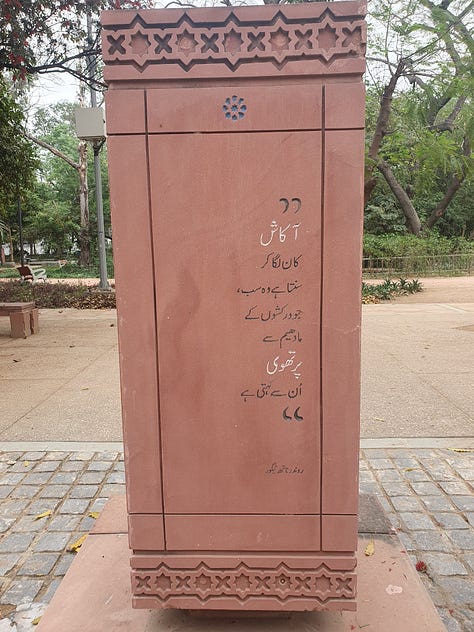

I spent a lot of time in gardens in Delhi, many of which are walled pleasure gardens originally built during the Mughal period (16th-18th centuries). I’d be walking along a path and suddenly come across an old tomb or a section of a wall from the 1600s. It was fascinating and delightful, having two of my great loves—history and nature—come together in one place. This is a neighbourhood park near my family’s house, which contains a spring poetry garden featuring blocks inscribed with verses from Hafez, Rumi, Tagore and Khusrau:

It was springtime—delightfully cool compared to Singapore—and flowers were in bloom everywhere. The parks were filled with squirrels and stray dogs, groups of young people playing cricket, practising their dance moves or having picnics, families with their children, and elders going for walks.

Another garden I visited was Sunder Nursery (Bagh-e-Azim), which also dates from the Mughal period and has since been restored and expanded. We went around dusk and ate at a café on the lake, where you could hear peacocks calling as night fell. I enjoyed two cups of hot chai and a classic pav bhaji, my favourite Indian street dish after chaat.

Art and Culture

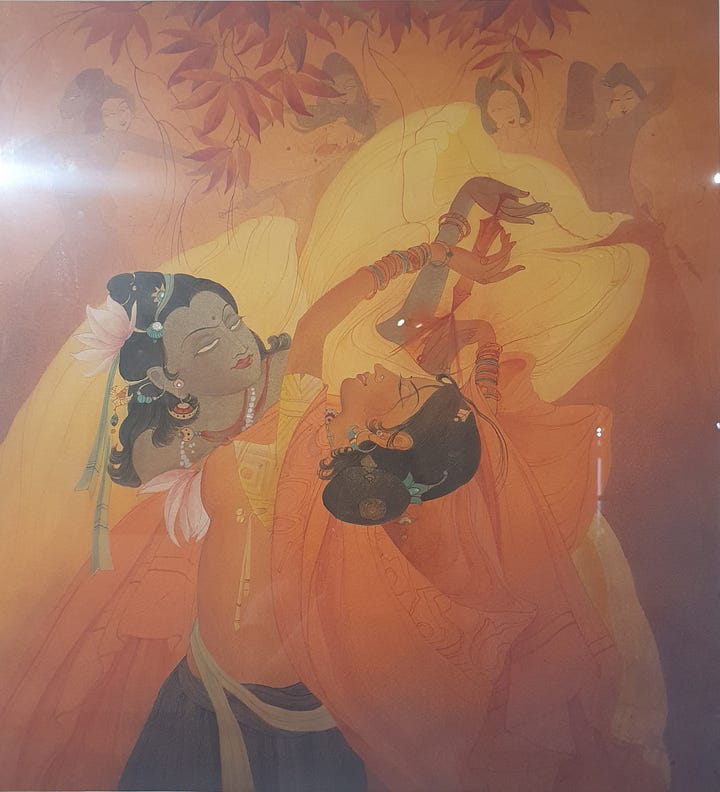

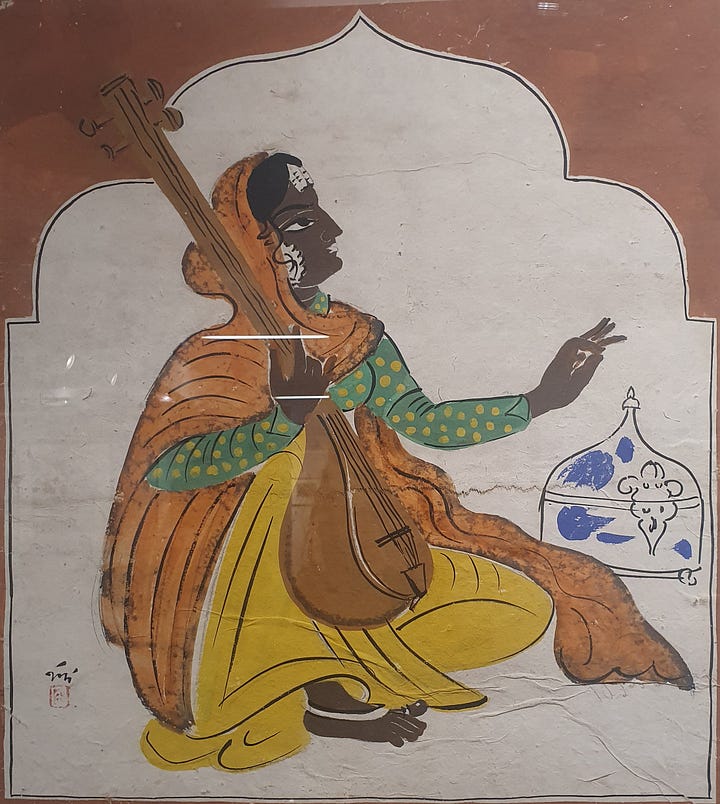

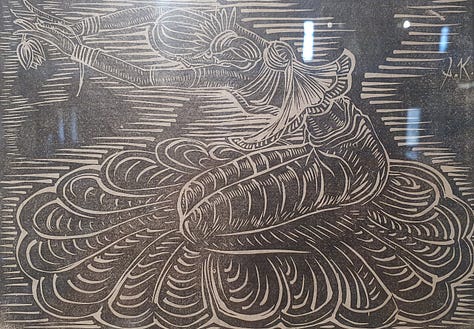

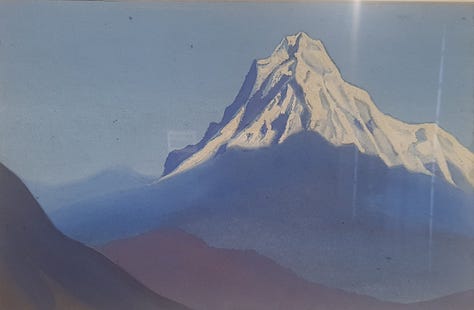

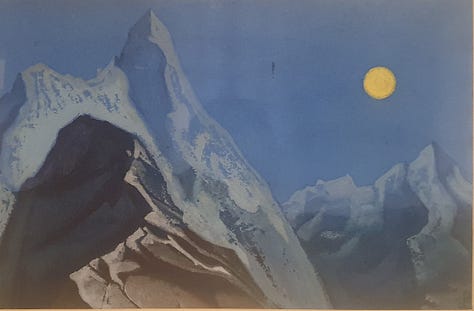

I also spent an afternoon at the National Gallery of Modern Art, which is located in a beautiful building called Jaipur House, the former residence of the Maharaja of Jaipur. The building was built in the 1930s by the brothers Blomfield, who were contemporaries of Edwin Lutyens, the chief architect of colonial-era Delhi.

Aside from the architecture and the gardens, it is home to a selection of rich and evocative artwork from India’s greatest modern artists. I don’t know if it’s because of my cultural heritage, but I felt the emotional impact of the art much more deeply than I expected to. It may also be because evoking emotional states (bhava) is at the heart of Indian art.

Sometimes I wonder if that’s one gift that India could offer the world, from its history and spiritual traditions: how to deeply feel everything, to engage with the emotional richness of life as a path to meaning. Other gifts of the subcontinent include boundless creativity and a unique flexibility of thinking, that I believe comes from our non-dual traditions.

Here are some photos of the art I most enjoyed (apologies for the mediocre quality, it’s hard to take good pictures in museum lighting, and anyway art is better in person.)

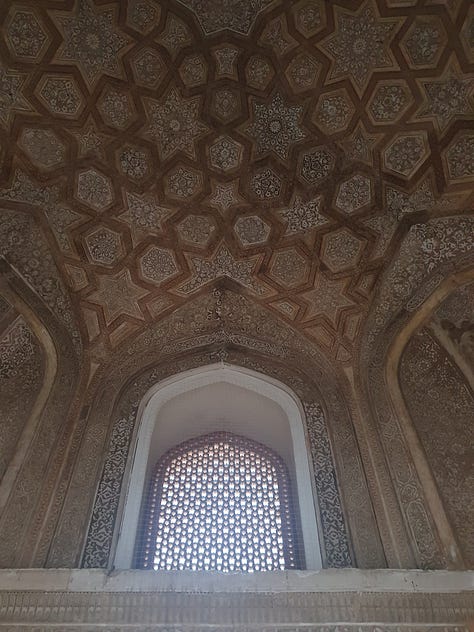

Finally, I spent an afternoon in Lodhi Gardens, a park from the time of the Delhi Sultanate (13th-16th centuries). It contains the tombs of Mohammed Shah and Sikander Lodi, as well as two other constructions, the Bada Gumbad (a mosque) and the Shisha Gumbad (another tomb, residents unknown).

Wandering through all these old tombs, I felt a haunting sense of abandonment. It was like the stones were asking: where have my people gone? The only ones who seemed at home were the pigeons and the dogs. My fellow humans, on the other hand, were occupied with taking Instagram photos, canoodling and chasing their kids around. There was graffiti all over the old walls (‘Deepak loves Priya’ ‘JM was here 2022’ etc.), and a security guard had to tell a couple off for setting up their picnic inside one of the cloistered archways.

Yet there was something beautiful about the decay too; 500 years on, these constructions, even covered in pigeon poop and inane scrawlings, are still so mesmerising. Show me a building from our time that will look as good as these do, half a millenium from now. Not to mention how incredibly generous it is to build a park for people to enjoy, in remembrance of someone who is gone from this world.

Life and death come together in tomb gardens in a way that is wise and comforting. When I’m in grief, I turn to the cycles of nature to help me through that winter of the heart. The tomb garden is a physical symbol of the healing process, a place where we can be reminded of the circle of life. The Mughals saw transcendence in the ordered, geometric layout of the garden, containing every delight known to us, and thus meant to resemble paradise. I see it in the way all the life of nature surrounds death, and is born out of it.

I leave you with a verse from Ghalib, one of Delhi’s most renowned poets:

Though I do not understand her words and may not know her heart Is it not enough that one so beautiful now speaks to me?

I hope you enjoyed this little detour through Delhi with me. Feel free to leave your thoughts and comments on any of my images or words, and to share this post with any who might appreciate it. From the next post, I will return to my essays on stress and how to deal with it. Subscribe for that and more.

According to Wikipedia, there are 5,500 temples in Vrindavan. This is probably an exaggeration, though maybe not by much. If it were true, given the town has less than 100,000 residents, that would mean 1 temple for every 18 people.