Over the past month I’ve met a number of people who are suffering from anxiety, and seeking out breathwork and meditation to help with it. When I encounter anxious people, I feel sad not only for their suffering, which is considerable, but for what we are all missing out on as a result of it. A person who is stuck in loops of fear and worry loses access to their own deeper self and potential; their talents and their creativity, their personality and unique perspectives—everything is twisted out of shape and smothered under the blanket of tension that characterises anxiety.

Some years ago, I watched an interview with Stephen Porges1, creator of Polyvagal Theory, in which he said that one of his driving questions is: what would the world look like if everyone knew what it was to feel safe? In other words, if every human on the planet knew how to access a felt sense of safety, what kind of world could we create? On the other hand, what does the world look like today, when more and more people do not feel safe, and have no idea how to get themselves to feel safe?2 (A parallel and equally important question is: what does the world look like from the perspective of someone who feels safe, versus someone who doesn’t?)

About a decade ago, at the age of 19, I moved to Barcelona for a year abroad, part of my university degree since I studied languages. I had moved countries many times before, but this was my first time doing it alone, and my first time in Spain. Despite my excitement at the novelty of the experience, my first few weeks were a haze of anxiety and panic. I struggled to navigate a foreign land, culture and language, a new job, and the process of trying to find a place to live. I couldn’t eat properly, I had very little energy, and everything seemed overwhelming and strange. I felt brittle, as if even the smallest things—like speaking with a potential housemate, figuring out which train to take, or buying dental floss—would break me.

Looking back on my younger self, I realise that I had no idea what to do to help myself, or how to understand what had happened to me. The anxiety had come out of nowhere, and all I wanted was for it to go away so I could be myself again. Thankfully, with the support of my family, and once I settled into a new apartment and my job, I recovered. Over the months, the city and its people grew on me, and despite that rough start, by the end of my stay I didn’t want to leave. Ten years later, Barcelona remains one of my favourite places in the world, and I can’t recall it without a smile on my face.

I share this not to suggest that anxiety can always be overcome, or that mastering it inevitably leads to beautiful experiences. To be honest, I don’t think that’s how it works, and my experience with anxiety is still something of a mystery to me. I don’t know what exactly I did to get past it, or whether it receded simply by grace. But over the years since then, I’ve come to learn a lot about how human bodies work: why we feel the way we do, what we need to live well and thrive, how to shift from one state of being to another, and much more.

This series of posts is my way of expressing all the things that I wish I could’ve told my 19-year-old self when she was going through that ordeal. It is structured as follows:

Theory. This first post will outline helpful perspectives on anxiety from a variety of different sources. Understanding yourself and the nature of anxiety is an important first step in discerning what to accept and what to transform. It will also empower you to know whether what you’re doing is perpetuating your anxiety or liberating you from it.

Practice. Subsequent posts will offer a toolkit of practices, including lifestyle considerations, that you can use to support yourself, or anyone around you, when anxiety arises. These are based on the theory of the first post and in many cases will be directly linked to one or more of the perspectives here.

Beyond. In this post I will wrap-up and offer my thoughts about the psychological and spiritual dimensions of anxiety. What themes does it bring up in us, what do we need to work with it, and how do we cultivate such qualities within ourselves?

Given that (1) increasing numbers of young people are dealing with anxiety, and (2) anxiety makes it hard to absorb information, I will be keeping everything as simple and readable as possible. If I use any technical terms, they will be in bold and I will explain what they mean. Feel free to read only what interests you, to re-read as many times as you like, and to take this in at your own pace, in your own way.

Disclaimer: Nothing I say should be taken as diagnostic or prescriptive—it’s just my experience, and my ideas. If you are suffering from anxiety, please seek out help from a trusted and experienced professional. In the meantime, or in addition, feel free to use my words as a gateway to understanding and exploring your experience more deeply.

What is anxiety?: a few perspectives

Anxiety is a natural human response to circumstances that are overwhelming, chaotic, unstable or in which you have no control. Sometimes the ‘trigger’ is limited and the anxiety is acute and short-term—as in my case, moving to a new country. Other times the trigger is chronic, such as an unstable job, a difficult relationship, a prolonged illness, or a period of stress or loneliness. A single trigger can also lead to long-term anxiety if feelings or circumstances are unresolved, or you are unable to return to a felt state of safety.

Anxiety is both an emotion and a state of being, and it can be experienced anywhere on a spectrum from mild worry to all-out panic.

physiological perspectives

your nervous system

From the perspective of your nervous system, anxiety is a manifestation of your mobilisation or stress response, aka. fight-flight-freeze or sympathetic dominance. When you encounter a stressful stimulus, your body tries to protect you and keep you safe by getting you to (1) run away, (2) fight your way out, (3) freeze or hide, or (4) befriend or pacify your opponent. All of these are survival strategies that your nervous system slips into instinctively, without forethought or consideration. In other words, you do not choose your response at this point.

You also do not choose to consider something stressful or not. You cannot will yourself to believe that a situation is safe when you don’t feel safe in it. There was nothing objectively dangerous about the city of Barcelona, but I still felt anxious there because it was new to me. I could (and did) berate myself to just “be more like everyone else who seems to be enjoying themselves without a care in the world”—but it doesn’t work that way.

Anxiety is physiological, ie. your body determines your response, based on prior patterns and conditioning. However, this doesn’t mean you can’t do anything about it. On the contrary, once you understand this, you also understand that your job when you feel anxious (assuming there is no real threat to you) is to down-regulate, or get your body to feel safe and relaxed again. If your anxiety is chronic, then your job is to consistently practice down-regulating until you build up your inner reservoirs of safety and ease, so that you can handle the outer circumstances you find yourself in.

The ‘opposite’ of the mobilisation response is called the relaxation response, rest-and-digest mode, or parasympathetic dominance. This is the state you are in when you are deeply relaxed, at ease, comfortable in your own skin and in the world. One of the major nerves involved in this response is your vagus (‘wandering’) nerve, so-called because it is a long nerve that wanders around and through your ears, tongue, vocal passages, heart and lungs, and into your gut. Many self-soothing practices—from self-massage to various forms of breathing and sensory awareness—are aimed at activating this nerve pathway.

your brain

Inside your brain are billions of brain cells, which use electrical signals of different wavelengths or frequencies to communicate with each other. Different kinds of cells use different signals at different times: like the various instruments in an orchestra playing a symphony. Your brain is singing—right now, and all your life.

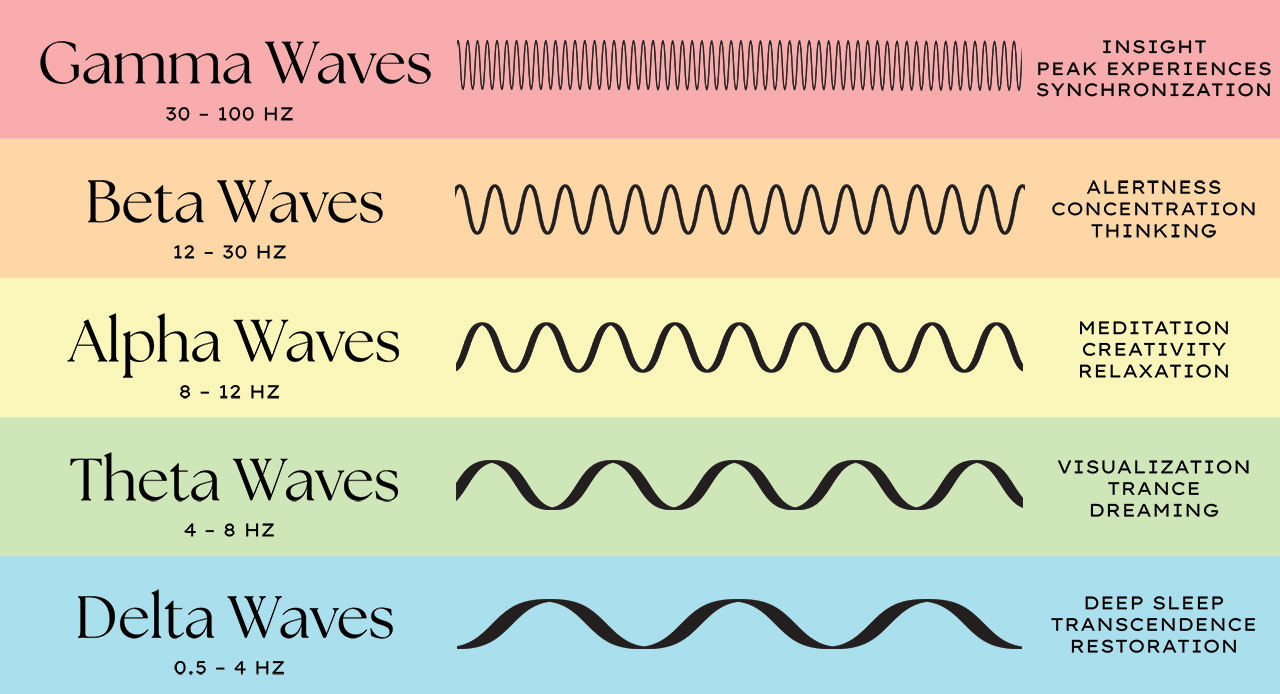

Scientists have measured and given names to the various brainwave frequencies, as shown below:

Many people assume (as I once did) that the whole brain is in one frequency at one time. That’s not the case. Rather, different areas of the brain are producing different wavelengths at the same time—hence my symphony metaphor. As with all things, the right balance between the frequencies, and the ability to move freely up and down the wavelengths, is critical for health and functioning. Too much or too little of any wavelength, or a part of the brain getting stuck in one wavelength, leads to problems.

Anxiety is correlated with a predominance in the higher wavelengths (beta and gamma), and a decrease or an inability to access lower wavelengths (alpha, theta and delta). Practices, tools and lifestyle considerations that activate and make space for the lower wavelengths can therefore be used to reduce anxiety. It’s like waking up the dormant instruments in your orchestra and tuning your brain to a new song.

your body

Your body experiences anxiety as an upsurge of energy with no clear outlet. Often there is also a layer of tension and constriction over the top, which stops that extra energy from being able to flow out of you and be expressed through action. It’s like a box that’s been pumped full of air, sealed shut and shaken up. This manifests as feeling jittery, twitchy or jangled. You are oversensitive to stimulation and unable to relax, a state known as hypervigilance or hyperarousal.

With anxiety, there is a mismatch between the level of your response and the situation you are in—as if you’re trying to drive a sports car at 100mph through tiny winding country lanes. Many of the mental and emotional layers of anxiety are versions of the physiological, nervous system states I mentioned above. For example:

You feel restless and jittery, or your energy swings up and down wildly (fight)

Your mind is racing with thoughts and ideas (fight), or it goes utterly blank (freeze)

You feel like you want to do something, anything—but you don’t know what to do (fight-freeze response)

You want to run away and hide, but even when you do, you can’t seem to calm down (flight)

You become needy and clingy towards others, and upset or agitated when alone (befriend)

You become obsessed or fixated on some things to the exclusion of others, and can’t regain proper perspective (hypervigilance)

The longer you remain in such a state, the more tiring it is, even though you may not feel it, because your nervous system is overriding fatigue to try to get you to act and protect yourself. You can’t seem to relax and release fully, even though underneath all the buzz, your body is tired from maintaining the activated state you’re in.

elemental perspectives

ayurveda

From the perspective of ayurveda, anxiety is an excess of vata dosha; in other words, there is too much air and space in your body and/or in your life. Air is a mobile element, with little to no stability or substance to it, while space is the absence of solidity and structure. This is why you feel ungrounded, spacey, out of touch with reality, disassociated from your body. It is also why thoughts go into overdrive, as overthinking (too much movement of the mind) is a hallmark of the vata type.

If you are already a vata type, or have a lot of vata energy in you, you will be more prone to react to stressful situations with anxiety (rather than say, anger or depression). If you want to be certain of your type, and get helpful suggestions about how to work with it, consult an ayurvedic practitioner. But if you are game to try and figure it out yourself, you can start with a basic questionnaire like this one.

traditional chinese medicine

In TCM, anxiety is an imbalance of the stomach-spleen meridian, and the Earth element. This is why being in a state of anxiety affects your digestion or appetite (‘butterflies in your stomach’), as well as your immunity (spleen). When anxiety veers into fear and panic, it also affects the kidney-bladder meridian, and Water element. The kidneys are right under your adrenal glands, which produce the adrenaline that sends you into the mobilisation response.

The kidneys are also very close to your psoas muscle, which instinctively contracts in response to perceived threats. An immobile psoas creates either (1) a braced, rounded posture of withdrawal and self-protection or (2) a forward-leaning posture that is paradoxically open and tense at the same time. The posture both reflects and perpetuates the state that inspired it.

Contrary to popular thought, I do not believe that stretching is the best way to work with the psoas, as it is usually done with too much vigor and too little awareness. The psoas is very sensitive and closely connected to your nervous system, so such an approach is likely to lock you out further and leave you wondering why any changes you do make don’t stick. Instead, we want to encourage the psoas to release the tension it is holding and restore its innate fluidity and suppleness. We do this, while attending to the sensations, psychological impressions and emotions that arise in the process. Practices relating to breathing, soft movement, sound and vibration, passive gravity-assisted relaxation, and even self-massage, done with deep, patient and gentle attention, work far better for this purpose and create long-term, tangible change.

energetics

In the yogic model of the body, anxiety arises from an imbalance in the lower energy centers (chakras), which are related to:

root: grounding, safety, sense of place and belonging

sacral: creative, sensual, instinctively relational, and sexual energy

solar plexus: personal power, boundaries and authority

You may notice overlapping—and occasionally contradicting—ideas between these three models and the physiological ones above. To me, this is a clue that they make sense, and are simply using different language to talk about the same state. I encourage you to take whatever serves you from any given model, and drop the rest.

Approaching a problem from multiple perspectives gives you the opportunity to learn something new, make fresh connections and diversify your thinking. The more nuanced your understanding, the deeper your awareness, and the more choices you will have when it comes to changing your experience.

Conclusion

I hope that some, if not all, of these perspectives make sense to you, and that it was worth going through them to gain clarity about your (or someone else’s) experience. There is a lot of information out there on this topic, but I tried to present a new perspective, drawing on my (rather eclectic) background and range of interests.

The next step is, of course, to find a practice that will transform your experience. I have compiled my best practices in the next posts in this series, which I will send out shortly—please subscribe to get them, or check my homepage in a week or so.

If you have any other perspectives on anxiety, either as someone who has experienced it, or as someone who has supported others through it—please feel free to share them in the comments. I also welcome any other thoughts, responses or questions on this topic.

If you know someone who is struggling with anxiety, please share this post (and/or the next ones) with them.

And if you appreciated this post or any other, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. As a reminder, my birthday promotion is still running:

I couldn’t find the interview in which he said exactly that, but this is the next-best thing, and one of his best interviews (in my opinion).

Note that he is talking about a person’s internal ability to manage their state; not that we should demand others behave in certain ways to make ourselves feel safe.

Thank you, as someone who lives with a partner who suffers anxiety, this makes total sense. More sense than many of the psychological explanations out there! Sadly, although he removed himself 3.5 years ago from the situation that triggered the anxiety, he still suffers from many of the responses you describe. We have tried many things, but his nervous system seems 'stuck' in the same pattern. I look forward to the next instalments.

Thank you, Vaishali, for this thoughtful and well researched essay on anxiety. It is very timely for me. After studying, practicing and teaching yoga for over 59 years, I am going back to my psychiatrist who I haven’t seen in 50 years to help me handle my anxiety. The world was in a terrible place then, a corrupt US president, the Viet Nam war to which friends were drafted and faced death and despair. I was in a difficult relationship and I was living away from my family. I was feeling very unsafe. I was put on medication and weaned off of it in less than a year and though my life has had many struggles, I did not feel the need for medication because I had a strong and vigorous yoga and spiritual practice - until now with similar circumstances occurring in the world and in my life. And my psychiatrist is still practicing! Though he is trying to retire. He sees some patients because there are so few psychiatrists available. So thank you for this. It gives me much to reflect on.