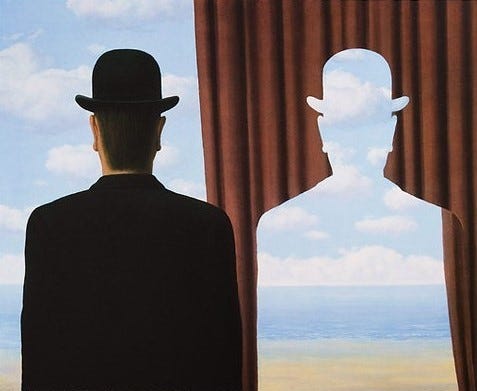

Sometime last year, I became aware of a niggling feeling that we are losing the distinction between what is real and what is not. The real world of bodies and buildings, earth and sky, sun and clouds and rain, is being mashed up and blended into the unreal world of screens, AIs, deepfakes, viral memes and virtual reality. Modern society is confused about many things, but the creeping insanity of this moment feels like something else entirely.

Not this, not that: a nondual perspective

Over the last few months, with the rise of AI, many people have explored and written about the technological revolution we are facing. This long piece is my favourite so far. As I’ve researched, I’ve noticed that discourse in this area lies on a spectrum between two polarities. There’s the YES end (which would traditionally be called desire or attachment), and the NO end (hatred or aversion), with much commingling in between.

On the YES end, the virtual world is full of exciting possibilities, and the more it converges with the real world, the more anticipation there is. (Anticipation for what, is a good question.) People are fascinated, enchanted even, by the seeming miracle of what we’ve created: how fast it is, how comprehensive, how it ‘learns’ from its mistakes, how well it simulates being human.

I had a conversation with someone who believes that every aspect of embodied life—all of our senses including touch and physical sensations, the felt sense that you are somewhere, with someone, our marvellous gut brain, instincts and intuition—will be perfectly replicated by technology, one day. I’m doubtful, not to mention I don’t really see the point. We’ve already got all that in this body, right here, right now. Why try to recreate it in all these complicated ways somewhere else?1

The NO end believes that the rise of AI, VR and the metaverse is sinister and evil, something to be feared and fought (example here). Interestingly, many who work in technology straddle these two poles: they recognize the dangers, feel them strongly, and yet choose to continue anyway, as if compelled by some hidden urge.

The whole conversation is dualistic because it separates things into good and bad, desirable and undesirable. Even the middle ground is still the result of combining some good things and some bad things, meaning it is still contingent on a dualistic paradigm. The nondual approach is beyond all this entirely: it is neither this, nor that,2 neither YES nor NO. Both at the same time, perhaps, or something else entirely. It’s that ‘something else’ that I’m trying to point to in this series. To do that, I’d like to bring in the concept of maya, from Asian thinking.

The many faces of maya

Maya is the idea that the world that we see all around us is illusory, deceptive, not what it seems. The implicit invitation of the teaching of maya is to look deeper, go further, seek the essence.

The popular culture version of maya is the Matrix, and the path that Neo walks is the path of freedom (moksha) from illusion. Perhaps that’s why I always associate the phrase ‘virtual reality’ with maya.

Like all Sanskrit words, maya has many different but overlapping definitions. In bold are words that might remind you of the virtual world:

माया · maya

an unreal or illusory image, a phantom or apparition;

illusion, unreality, deception, jugglery, sorcery, tricks, witchcraft and fraud;

a magic show, where things appear to be present but are not what they seem;

the power or principle that conceals the true character of spiritual reality;

that which exists, but is constantly changing and thus is spiritually unreal;

(archaic) extraordinary or supernatural power and wisdom; the wondrous and mysterious power to turn an idea into a physical reality

(possible root) to mystify, confuse, intoxicate, delude; to disappear, be lost

(proper noun) a name for Lakshmi, the goddess of abundance; the name of the mother of Gautama Buddha

Broadly speaking, maya has two guises: beguiling enchantment (the positive) and deceptive trickery (the negative). Sometimes it also refers to dualistic thinking—meaning that when we are stuck in binaries, we are only perceiving maya and not the reality behind it. This has been a hugely important reminder for me in all kinds of contexts, because so much of our thinking is dualistic and therefore never really accurate.3 Even the idea that I used to start this article (real world vs. unreal world) is dualistic. My perception that the two worlds are dissolving into each other is what drove me to include the theme of nonduality in this series.

Maya is the perfect metaphor to explore virtuality, because they are astonishingly similar in so many ways. As we explore, I’ll do my best to take a nondual approach—neither unreservedly embracing nor completely denying—because the virtual world, like everything else, is neither one way nor the other, but both at the same time, and more.

The purpose of the teaching of maya is to point us beyond two to one, or beyond forms to the greater and more mysterious reality behind them. The message is to avoid getting caught up in the beauty and the drama of the illusion, and instead look deeper, to the essence. Throughout this series, I will therefore also suggest ‘ways out’ of the maya of virtuality, based on my own experience of navigating online spaces. In creating these little ‘emergency exit’ behaviors for myself, I was very inspired by the Zen approach—simple, aimed at the heart, and not taken too seriously. That’s the spirit in which I offer them to you.

Maya as deception

Maya is often seen as a negative force that tricks and ensnares us in endless cycles of suffering with no way out to freedom. In ordinary life, the illusion of maya is broken and the veil is lifted ‘accidentally’ in intense or charged circumstances, as when we are close to death, in grief or great shock. This is when we see the true nature of things: that they are fleeting, with no inherent substance to them. Everything is contingent on everything else, all is interconnected. The realisation is usually bittersweet, and like all things, tends not to last, though it can be deeply transformative. Most of the people I know who are drawn to spirituality—including myself—came to it through tragedy.

This dewdrop world –

Is a dewdrop world,

And yet, and yet…

—Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828), Japanese Zen poet

This haiku was written upon the death of his daughter.We can also get glimpses of reality beyond maya in moments of spaciousness, when we settle and go beyond the surface-level thoughts, ideas, beliefs, and feelings that we’re always spinning through. Hence, meditation.

Self and World

There are so many ways that the virtual world propagates delusion and deception that I can’t go through them all. The one I want to focus on here is the way it confuses and warps our perception of self.

Virtual spaces alienate us from the reality of physical existence: both our bodies, and the physical world around us. From infancy through adolescence, we learn who we are by relating to the world through our bodies. The physical, felt body is intrinsic to identity. This is why death is so frightening; it’s the end of the body, our first home in this life. Of course, many spiritual traditions advise you to transcend the body—but I’m not sure they meant for that to happen via VR.

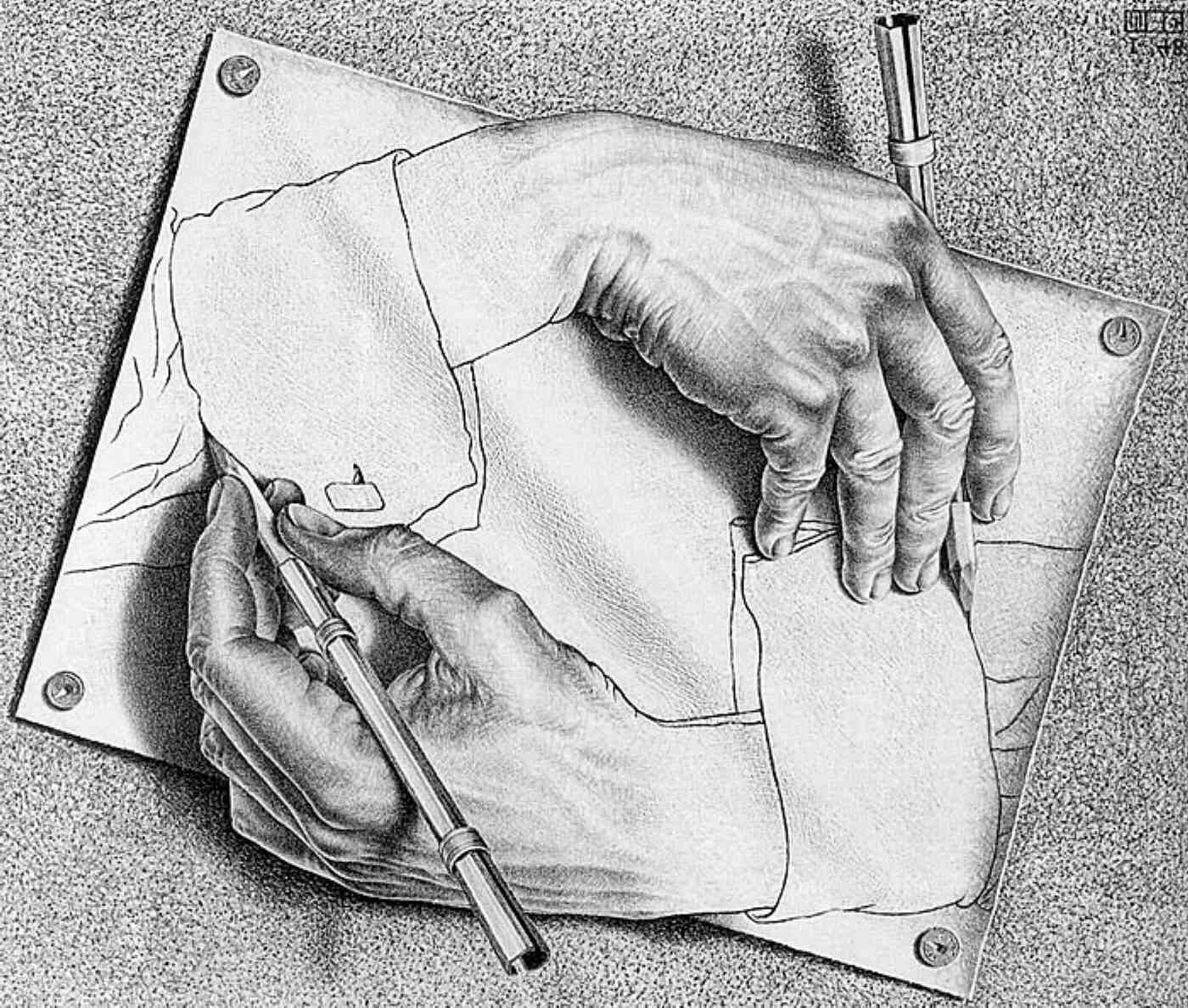

The fundamental issue that the virtual self brings up is the difference between how we perceive ourselves inwardly and how we appear outwardly. Who am I, as I sit in front of a screen and write these words? Who are you, as you read them? Are you the avatar, or the person behind it? Are you the face that appears in the selfie, or are you the one taking the selfie? Or are you both? And if you are both, how well do you integrate the two? These questions can be a gateway into deeper self-awareness, or, more troublingly, into alienation and delusion. Recall that one possible root of maya is to delude, to disappear, to be lost. This is the inevitable result of erasing the inner self in pursuit of the outer one.

A few years ago I watched Altered Carbon, a futuristic series in which humans gain control over birth and death, reincarnating through technological means. Each person’s consciousness gets downloaded into a little disk that can be removed and inserted into different bodies ad infinitum. (The bodies are called ‘sleeves’, which is simultaneously true and awful.) This is the endpoint of transhumanism, and the world that results is utterly dystopian, depraved and inhumane.

The show is doubly interesting for the way it explores ideas of self- and personhood. In this world, there are some who still believe in an immortal soul and therefore choose to live only once. Meanwhile, the ultra-rich return over and over again in clones of their own bodies, becoming unhinged even as they rule the world. Regular people get to ‘re-sleeve’ if they can afford it, and criminals are temporarily killed (their consciousness ‘shut down’ for the duration of their sentence) while their bodies are sold off and used as hosts for anyone who can pay. There is a scene in the first season which sums up both the horror and the promise it came from:

Where is the voice that said altered carbon would free us from the cells of our flesh? The visions that said we would be angels. Instead, we became hungry for things that reality could no longer offer. The lines blurred… You want to know who I work for? The people who understood that, who used it to become wealthy beyond words in the only currency that truly matters: the appetites of the immortal.

It’s a very dark show, but worth watching for the insights if you can stomach it. Thankfully, we don’t live in that world, but even in ours we see the way that virtual technologies compress us down to an image of ourselves, and thus reinforce ego and the persona over humanity. Some have said that the more visually screen-oriented society becomes, the more shallow and narcissistic we become. Not a very hopeful outlook.

The technology per se is not the problem so much as our identification with it. We are stuck in the maya of believing that we are what we see on the screen, and nothing more. By now it should be obvious to us that bodies on screens are fundamentally different from bodies in physical space, whether we’re talking about ourselves or someone else. We can’t pinpoint what the difference is (it’s embodied presence, something we don’t have a language for and therefore much awareness of), but we feel it, and we are at risk of losing our sanity if we don’t acknowledge it.

When I was away from my family at university, we used to video call to keep in touch. I remember that seeing them on screen and not being able to be with them made me feel homesick in a way that speaking on the phone didn’t. A voice on the phone felt like a warm, familiar presence in the room. Paradoxically, video technology brought us closer in the moment, but I felt further away, and much lonelier, the moment we disconnected the call.

In the past century we’ve gone from still images in photographs to moving images with sound in videos. In the future perhaps we will have holograms and ways to integrate the other senses into our virtual persona, such as touch through haptic technology. The underlying assumption and assurance is always that the more technology advances, the better it will be at replacing reality. But is that really true? I think we’ve hit the point at which further development detracts as much as, if not more than, it adds—most of us just don’t see it yet, because what we lose on the way is intangible and therefore, forgettable.

Ways Out

There are, thankfully, numerous ways out of this maze of deluded fantasies. Central to all of them is reclaiming the human dimension, which means the embodied, feeling dimension of being. Don’t let yourself get cut off from yourself, in other words. When I’m interacting online, whether it’s by email or on social media, I am always trying to touch the human behind the screen. This applies both to yourself and the one you’re talking to. With the rise of AI-generated content, it becomes even more important to communicate from the heart. Let the technology be a means for two humans, or two hearts, to meet; rather than an end in itself.

Another practice I use, particularly when I find myself consuming a lot of online media (videos, TV shows, scrolling), is to return to the living process. You are a life form, in the process of being and becoming. You are not a static self, passively imbibing like a machine. Everything transforms you. So, as you scroll and watch and read, ask yourself:

How am I being? desperate, stubborn, lazy, closed… generous, confident, pure, free

What am I becoming? addicted, nervous, tired, unfeeling… informed, empowered, inspired, connected

Finally, I invite us all to become more aware of the multiplicity of selves that we are. The online self is part of us, not the whole of us. It needs grounding in the physical self, or we risk going crazy. When we accept that and give ourselves space, we also find the power to establish healthy boundaries, and to organize and integrate our selves more deeply.

Conclusion

As I am unravelling my own thoughts on this topic, there is one key theme I keep returning to. Both maya and the virtual world are equally dangerous in their ability to ‘delude, mystify, intoxicate’; but at the same time, both present us with an opportunity to connect with the insubstantiality, and therefore the mystery, of who we really are. I will return to this idea more in my next posts, where I will focus on the more positive dimensions of maya and the virtual world—ideas of magic, play, dreams, and mystery. Stay tuned and subscribe to get those directly in your inbox.

Thank you for reading. I have spent longer on this article than any other so far, going through numerous rewrites as I tried to clarify my thinking. As always, I’d love to hear your views on anything I said.

And to say thank you and support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. More on that here.

Later I found out that according to Einstein, acceleration (and therefore gravity, a key element of embodied experience) can never be simulated. If this is true, my skepticism puts me in good company.

This is a translation of neti, neti, a Sanskrit phrase used in philosophical debate and teachings. It negates all apparent forms to try to point out what is beyond them.

Tangentially, I believe that thinking from the heart (creative, imaginative and lateral thinking) is intrinsically nondual, while thinking from the brain tends to be more linear, analytical, discrete and therefore dualistic. This is a powerful interview I watched recently that goes into these two modes in more detail, from a Western neuroscientific lens.

Aloha Sista 🌈🐬

Mahalo fo putting so much time an heart inta yur works. Look forward ta reading more.

Blessings yur way🌺

Maya has already placed the eternal living being in a machine made of matter controlled by the material AI of mind, intelligence and false ego (identification that I am the machine). Real means eternal and false means temporary. The universe and everything in it (aside from the eternal living being) is temporary. Maya covers our original spiritual consciousness, that I am eternally an individual living being.