This is the third post in a series on ideas to keep you sane. Each post is standalone, but if you missed them, you can read the first post here and the second post here.

how much self-awareness is really helpful?

I recently had a revelation during weight training about the difference between internal and external ways of seeing, and how they tie into self-awareness.

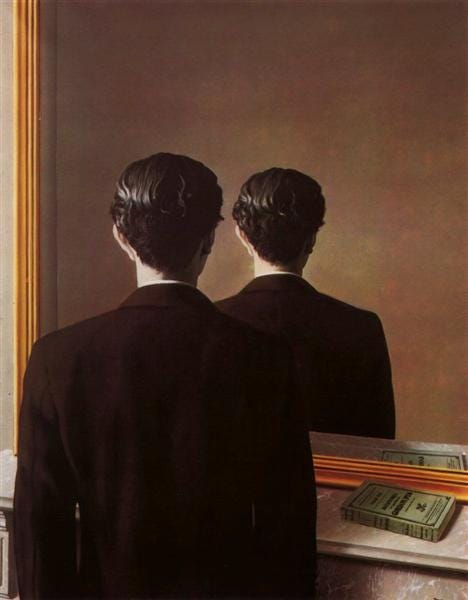

The background is as follows: My current movement space has a mirror that I started using to look at my technique as I swing my kettlebells. I haven’t trained with a mirror since my early teens, when I was dancing ballet; and one of the reasons I eventually gave ballet up was the excessively external perspective in the way I was taught. It was too much about how it looked, and too little about how it felt. That disconnect led me to other forms of movement that emphasised connection and relationship, either with others (team sports like football), with self (yoga and somatics), or with environment (swimming).

Anyway, for about three weeks or so, I was using the mirror during training as a live feedback tool. Initially I found it quite fascinating, because I could immediately see certain patterns and tendencies that I hadn’t noticed before, and then ‘correct’ them in the moment. But after a few sessions, I realised that if I faced away from the mirror while swinging, I started to feel a bit panicky and lost, not quite as in control of the weight as I normally am. And then I noticed that the way I was swinging while watching myself created a certain fixation in my eyes and head, which in turn led to an uncomfortable ache in my neck the next day.

Long story short, the act of looking at myself while doing something, while initially helpful, ended up creating more problems than it solved. First, I lost touch with other somato-sensory inputs that were giving me a more spontaneous mastery of the movements in question; and second, I became fixated on what I was seeing to the point of rigidity and tension.1

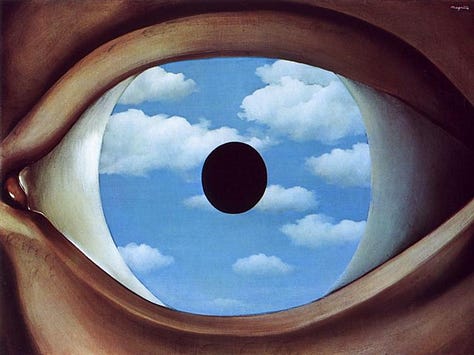

Everything we see hides another thing; we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.

—Rene Magritte

applications

The reason I find this idea so interesting is because it parallels so much of the work I do with meditation and self-awareness. It boils down to the question: how much self-awareness is really helpful?2 As I wrote about in my previous post, more is not always better. Too much self-awareness becomes more like self-consciousness: being caught in our own narratives, beliefs, thought spirals, reactions until we feel overwhelmed and can’t actually do anything spontaneously. In simpler terms: paralysis by analysis.3

In the language of Laban movement, we are talking about the spectrum of Flow, which ranges from Free to Bound. In Free Flow, we are uninhibited, responsive, spontaneous, fluid, allowing things to happen organically and naturally. In Bound Flow, we introduce control, management, a certain amount of tone or tension, so that movement becomes targeted, restrained, fixed or even inhibited. As with all other things, we each have preferences and habits around the kind of Flow we use and inhabit in life. Sometimes Binding is useful, other times Freeing is useful; it depends on context and intention.

When there is too much Binding or control, we lose trust in our instincts and habits, in part because awareness becomes a correcting mechanism rather than simple witnessing. I have noticed this tendency in both meditators and people who have been in therapy. In making what is unconscious conscious, we gain perspective, and perhaps a certain kind of liberation. But we also lose the ability to improvise, to speak and think and act freely, and to trust what emerges out of our natural, uncontrolled self.

zooming out

I believe we are going through such a process collectively and generationally, in many different domains of life. Younger generations are becoming aware by questioning the unconscious patterns of older generations, in areas as diverse as work, partnerships and marriage, relationships to the earth, money and financial systems, religion and spirituality, meaning and purpose in life etc.

The problem is that becoming conscious is an extremely messy and uncertain process, with no guarantees of success. We cannot say for certain that being in conscious relationship to something is always better than being in unconscious relationship to it. Sometimes it is worth leaving things be, and trusting that the way we (or nature) does things, really is best. In other words, the hardest part of becoming self-aware is knowing when to let go of the self-awareness and just be.

Likewise, it can be deeply frustrating to realize something about yourself, to gain insight about a pattern or a tendency, and then not know what to do with that information. I was sitting in a park the other day when I suddenly recognised the shape of a pattern I have been carrying in my romantic relationships. But right after the insight landed, I also had the thought: now what? How does this help me? What do I do with this? The temptation for awareness to become corrective is immense and nearly impossible to resist. We are not content to simply witness, to attend without fiddling with this or that, or pushing in this or that direction. The missing ingredient here is acceptance; in its absence we default to (over)correction.

In traditional forms of meditation, there is a distinction between concentration (shamatha) and insight (vipassana). Concentration-based meditations, which now includes most forms of mindfulness training, have a corrective flair to them, because they are goal-oriented training tools. The point is to improve your attentional skills and focus. Insight-based meditations do not take this approach, because they are process-oriented awareness tools. But because many people begin with concentration training, they are unaware of how to let go of that self-conscious corrective tendency during insight practice, or even in life. Self-correction is an automatic impulse also fed by socio-cultural conditioning to try harder, be better, do more, keep growing, improve yourself.

The irony is that we cannot become who we are meant to be by watching ourselves, or controlling the process of getting there. A certain amount of flow and surrender are required for life to take you onwards, or for anything truly fresh to manifest. In my experience, these qualities are also required to live a happy life, free from the complications and burdens of overthinking and overanalysis.

In the past decade or more of meditation training, probably the most important thing I’ve learned is how to let go of control and trust myself. We train so that we can offer ourselves more and more space, so that we can surrender more and more deeply to the life moving through us.

I leave you with the reminder that self-reflection—no matter the form it takes— is about presence. It is about accompanying yourself through life, being your own ally or partner as you live. It is not about fixing yourself and not even necessarily about seeing anything about yourself. You do not need to make yourself learn or grow; you only need to be, and all that will happen spontaneously.

I acknowledge that there are many variables at play here. In this scenario, it was the fact of seeing myself in realtime in a mirror that became an issue. In other forms of training, I have worked with recorded video feedback, live feedback from a coach, and interoceptive feedback (ie. from myself to myself). All of these have been helpful in a way that wasn’t problematic. It seems that something about being reflected (1) externally, (2) to myself, (3) moment-by-moment, is where the danger, and the fascination, lies. I wrote more about this idea in my series on maya and the virtual self: see here and here.

In a previous post, I quoted meditation master Chogyam Trungpa talking about the distinction between self-awareness and consciousness. I reproduce the same passage here again, because it’s such a potent reminder:

It is as though somebody is standing behind you with a sharp sword. If you are not meditating properly, sitting still and upright, there will be someone behind you just about to strike. Or if you are not dealing with life properly, honestly, directly, someone is just about to hit you. This is the self-consciousness of watching yourself, observing yourself unnecessarily. Whatever we do is constantly being watched and censored. Actually it is not Big Brother who is watching; it is Big Me! Another aspect of me is watching me, behind me, just about to strike, just about to pinpoint my failure. There is no joy in this approach, no sense of humor at all.

You are so concerned about watching yourself and watching yourself watching, and watching yourself watching yourself watching. It goes on and on… What is really needed is for you to stop caring altogether, to completely drop the whole concern…You must remove the watcher and the very complicated bureaucracy he creates to insure that nothing is missed by central headquarters. Once we take away the watcher, there is a tremendous amount of space, because he and his bureaucracy take up so much room.

For an interesting take on how this feeds into anxiety and movement practice, check out this article by

.

Thank you. This piece has pulled on all sorts of threads yet there is something particular coming up for me, a half-remembered segment of a teacher speaking or from a book. Something about the mirror itself and how it reflects unconditionally whatever appears and leaning into that quality of the mirror rather than the appearances is the ‘practice’. It feels really helpful to have bee reminded of this image 😀

🙏🏼💖🌺🐝 lvzzzz