A quick side note: alongside Substack, I have recently (re)started posting content on Instagram. If you like shorter, snappier ideas, visual presentation, and/or want to be kept updated about my in-person life and teaching, feel free to follow me there. And of course, please subscribe here for longer posts like this one.

1 · 🌗 surrendering to friction

I’m writing this mostly as a note to self, but in the hope that you will also resonate. Things have felt sticky and full of friction lately; in other words, the going is getting rough, as it tends to do from time to time. The hardest thing right now is not the specific situations I’m in, or the details of what may be going wrong in this or that part of life. It’s bringing myself to actually accommodate the change in pace, the roughness, the challenge—to surrender, if I can use that word, instead of proceeding as usual and hoping for the best.

The question I ask myself is: what is the appropriate response to the grittiness of life? To being confronted by what is ugly, or what has failed, or what isn’t working and feels hopeless?

From a somatic perspective, when we are faced with challenge or threat, our bodies mobilise energy to meet and overcome that challenge.1 And then, once the challenge is past us, our bodies discharge that energy and recover. The trickiness comes in when we are faced with threats that we cannot overcome through action, either because there are too many, or because they are outside of our control. In these cases, mobilising energy is activated but never discharged—it keeps running through the system, making us increasingly jittery, anxious, annoyed. I’ve been calling this my hedgehog mode: in which I am prickly, and need space to be soothed.2

For humans in this mode, the default tendency is to express that mobilising energy by doing more, faster, right now (!!!) Time and space both compress into a frantic sense of pressure and urgency. While this level of drive can be useful and even fun to experience sometimes, when sustained too long, it crowds out other important and healthy qualities like ease, creativity, flow, play, rest and exploration… Moreover, any state we’re in drives our actions and also our perceptions, so that the world increasingly reflects back to us the same frenetic energy we are living by. This is an example of how states can become self-reinforcing feedback loops.

I’m realising, counterintuitively, that the thing that is being called for is the one that feels the least accessible in that moment: more time, more space, less fixation, a slower speed, more trust, generosity, a lighter touch. All the ways that you would soothe yourself if you were actually a hedgehog under threat.

What we are doing in this process is shifting our pattern of response from resistance to surrender, so that when friction arises, we meet it differently. We practice so that more and more, our default response to being activated, mobilised, triggered etc., becomes gentleness, space, kindness, curiosity, letting go. In other words, we meet prickles with care rather than more prickles.

2 · 🌕 pace and rhythm

Probably the single most underappreciated skill in life has to do with our abiity to meet, match and master our rhythms. We have both internal rhythms, perceived largely through fluctuations of energy, focus and mood; and external rhythms, which set the timings of our days, weeks, months and years. Feeling out of sync with any rhythm sets us up for the kind of tension and friction I described above.

The world we live in tends to accelerate more than slow down, and so many of us inevitably feel pressured and pushed into a faster rhythm than we would like to be in. Speediness is both a trigger and a characteristic of mobilisation. Becoming habituated to that state creates a temporal feedback loop where everything just keeps going faster and faster, and it therefore feels harder and harder to slow down.

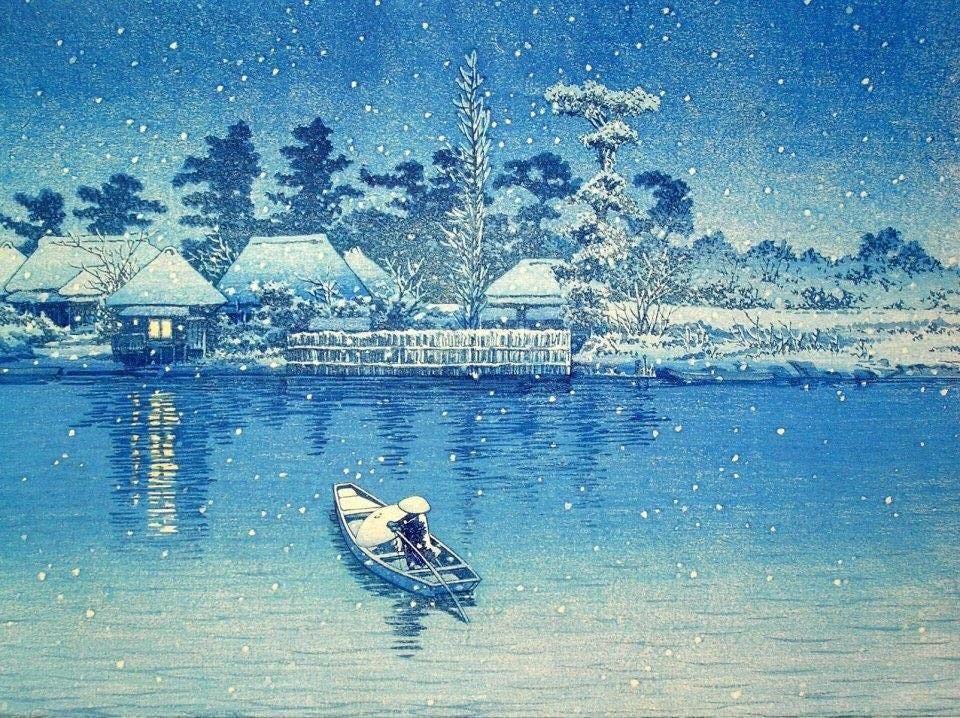

On the other hand, there are times in life when circumstances compel us to slow or even stop entirely: it could be an illness or injury, the loss of a job or some kind of slump in work, grief or bereavement, or even traveling to a different place or culture. Slowing down, whether intentionally or by necessity, requires a level of trust that most of us find hard to come by. We have to trust that life still happens just as richly and satisfyingly at that slower pace. And we have to trust that life will still be there, waiting for us when we recover or re-emerge from our (enforced) hibernation.

Another way to think about this is to recognize that slowness and speed are mutually supportive. Like all opposites, they co-create each other. We slow down and regain energy, so that we can move fast again. We move fast and tire ourselves out, and so the body will naturally seek rest and downtime to recover. And so on and so forth, in a cycle.

It is not that being fast or slow is necessarily better (though I would argue that speediness requires more skill to handle well). What we aim for is the ability to navigate and function well at many different rhythms: to make every speed possible and enjoyable to us. Our ally in this process is the ability to pace. When things speed up, we have capacity and energy to ramp up with them; when things slow down (or when we need to), we are able to ride that wave smoothly down. Throughout, we are surrendering to the pace of things, as they are, and ourselves, as we are.

Pacing feels like being generous with yourself and with how things are. It carries a sense of kindness inside it, that you’re willing to accommodate yourself and others. When we master the ability to pace, it also opens up an expansive sense of time around us and in our world. Alongside is the knowledge that you are unfazed by the natural up-and-down rhythm that life entails.

→ Music is a great way to get into this exploration, as we intuitively choose to listen to different kinds of music depending on our moods, energy levels and needs. We allow ourselves to be drawn towards and nourished by different tempos and paces in sound. Sometimes the rhythm of music syncs up with our bodies’ internal rhythms, meeting us on a level that is beyond words and concepts. Other times the rhythm of music will shift our internal rhythms, slowing us down or speeding us up effortlessly. Over time, surrendering to sound, song, music, becomes a way that we attune to and pace our own rhythms more deeply.

For other thoughts on this topic, check out this earlier post on rhythm, and this post from my series on anxiety where I discuss somatic rhythms.

3 · ☀️ choosing what is easy

There are so many ways in which we all drive ourselves towards doing what is hard. Some recent examples from when I’m teaching include being asked:

When I meditate, should I deliberately work on my difficult past memories? (No, there’s no need to do it consciously—when you’re ready to heal, those memories will arise and call for your attention on their own. All you need to do is make space for them at that time.)

Do I need to feel my physical pain more deeply, for it to heal? (A very interesting idea, with some truth to it. If you have the capacity and the skill to turn towards pain, it can sometimes ‘unlock’ and flow through and out of you more rapidly. But I wouldn’t recommend this as a general instuction, because most people don’t have the awareness or the ability to process such an experience.)

Perhaps I need to do more—excavate and articulate and analyse—my feelings about this or that challenge I faced, in order to learn and grow? (Again, all this will happen on its own if you just make space for it. There’s no need to do extra things with your problems.)

People also talk in this way about therapy, or about workouts, or in general about their journey of personal growth. It reminds me of the way in which we prod and poke at physical wounds as they heal—itching at scabs on our skin, or poking our tongue into toothy holes in the mouth. There is something ingrained (or conditioned) in our minds that continually takes us towards what is painful and difficult, so that we can solve it somehow. But often what happens instead is that we get caught in loops of negativity and pain, unable to see a way out. We pick at the wound so much it impedes the healing process.

This impulse is so deeply embedded in us that we unconsciously bring it into somatic practice, and especially into meditation—where it is frankly unhelpful and doesn’t belong. The richness and joy of somatics comes from the fact that it orients us towards ease, relaxation, dilation, expansion… and that out of such a change in state, a new, fresh life emerges. Things are healed and restored on their own. We are rejuvenated by the time we spend doing less, lying around, breathing, feeling, being natural and easy with ourselves. The world of somatics is an automatic and necessary counterbalance to the outer world that tells us: things are only worth it when they’re hard, or you need to push if you want to see results, and how you are right now is not good enough.

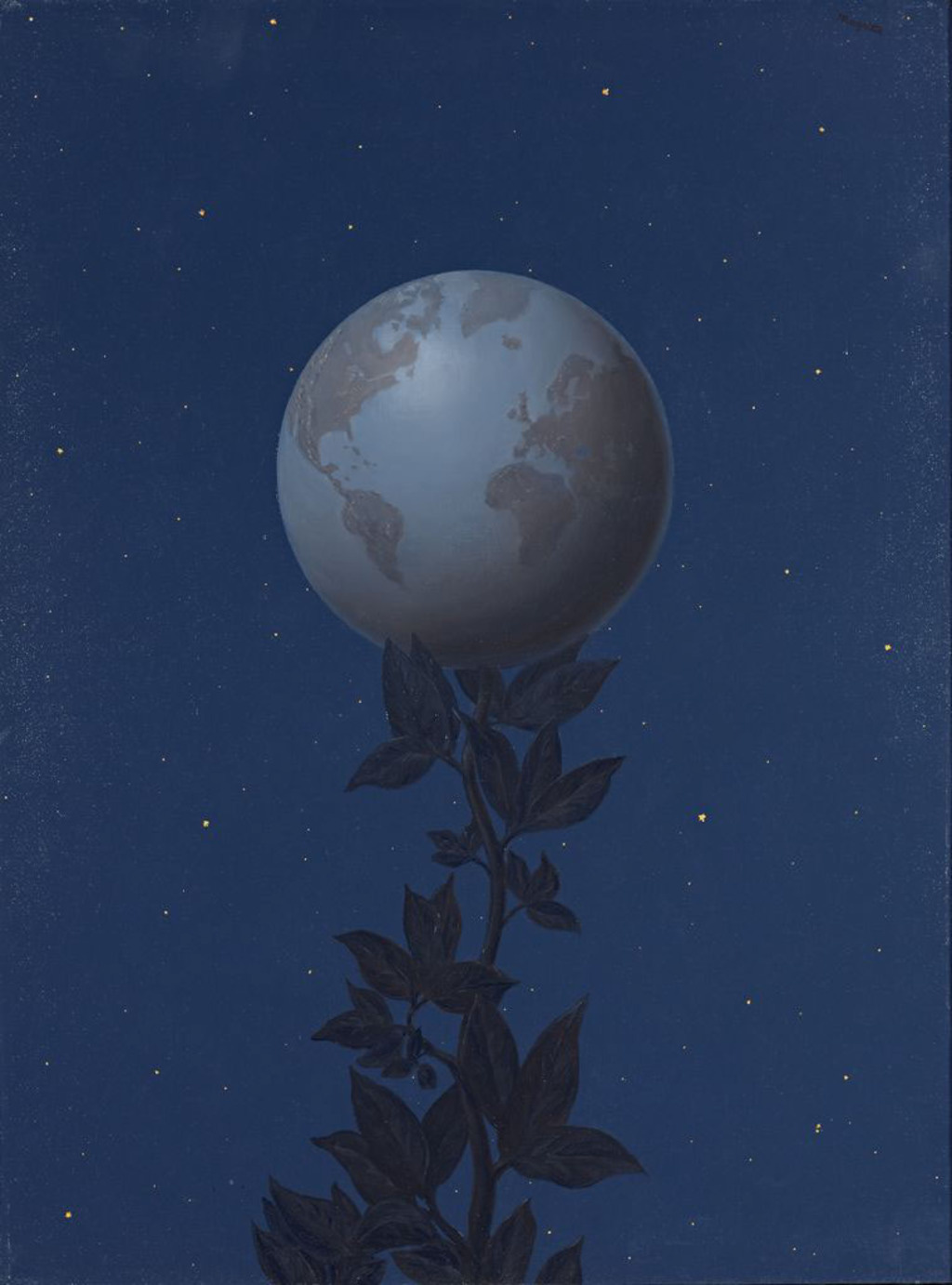

Somatics is about consciously choosing ease, as a way of learning how to be differently in the world. Crucially, it is not anti-growth but actually fosters an organic, innate, natural pattern of unfolding and expansion. Growth does happen through challenge and frustration, but it also and equally happens through ease and joy. It is both a reaching towards what we are not yet; and an instinct to be more of what we already are. In this balance I think of the way plants grow towards the sun—by instinct or tropism, unforced and unhurried yet still energetic and powerful.

Learning to be easy with what is hard is also the essence of the meditative journey. We begin with what is pleasureable and beautiful, and then grow to encompass what is neutral and even what is rough. Along the way we develop the microskill of being with what is, no matter what that is; and we develop the capacity to handle it all gracefully. The thing people miss is that it begins with finding what is easy, pleasurable, flowing, instinctive. It doesn’t begin by jumping into the deep end of what is hard and sticky right at the start. And even when we’re further along the path, we still continuously and consciously reorient to relaxation, to enjoyment and ease, because that is how we build capacity, and where our basic energy comes from. Over time we internalise in our bones that life force is inherently blissful—and that it is our birthright to be at ease in ourselves and in the world.

There is absolutely no shame in choosing what is easy. In fact, there is an enormous, instinctive wisdom in having a dedicated practice that values softness and un-doing of this kind. What we practice filters out into the rest of life, not by making us lazy or stagnating our growth: but by making what was hard before feel easier and easier, until we master it. Through somatics we make the process of growth simpler and more pleasurable, because we cooperate with our own instincts and the way the brain and body naturally like to learn.

I recognize that a lot of what I say and write makes little sense until you’ve experienced somatic practice for yourself. But I suppose that’s why I write about it—so that something in my words will resonate and spark the desire in you to try this out, or to deepen it, or to experience yourself differently.

Thank you for being with me all the way to the end of this post. I’d love to hear your thoughts, especially on what you do when things get hard.

This is only one potential response of many, though it may be the most common one. In some cases, we may not be able to mobilise and instead we collapse or shut down, numbing ourselves or dissociating from reality in order to cope. I won’t go into this response here, but it is equally valid, and equally instinctive (and therefore life-serving in its own way).

The other metaphor I use when I’m in this state is cactus mode: same kind of prickly but with a sense of space from the desert all around. It’s also easy to see with cacti that what lies inside the frustrated, prickly energy is fluidity (and therefore feeling) that sustains life. Embodying a cactus therefore involves honouring your self-protective needs and tendencies, while remembering what is under the surface of your irritation—usually a deeper emotion like hurt or sadness. When that deeper feeling is allowed to flow, the prickliness is discharged automatically.

Insightful analysis and well-written, plus nice art! Perhaps helpful, i recently read this line about Archangel Raphael in context of Kaballah (from "The Ladder of Lights" by William G. Gray) as it relates to your mention of "cannot overcome through action": "Creative use of thought is his specialty. With that art we may adapt ourselves to any circumstances, and then discover how to adapt circumstances to ourselves. That is Hermeticism at its height. We need not fear being hurt while Raphael remains to heal."

I so resonate, thank you. I practice a somatic body work which does just this - doing what is easy, what flows and just 'being with' what comes up in the experience...can lead to deep awareness and healing.