Time, Change and Capacity

An Embodied Guide to Anxiety (V)

This is the fifth and final part in a series on embodiment and anxiety. For background and context, read Part I. For practice ideas, read Part II, Part III and Part IV.

In this post, I offer my thoughts on the deeper psychological and spiritual message that anxiety evokes. These are themes that I’ve reflected upon during my own experiences with anxiety, and that I’ve supported others to explore. If you are like me, going deeper is a way to find meaning, and meaning is how we knit the broken pieces of ourselves into a new whole. Going through anxiety transforms us, if we let it. And sometimes, though not always, the identity that emerges on the other side is stronger and softer, and truer to self.

The ideas in this post are somewhat abstract; therefore with each theme I am including a practical lifestyle suggestion (signified by →) to bring its central message back down to earth. Hopefully these ideas will be novel and fresh enough to offer you new ways out of, or through, your experience of anxiety.

You may notice that many of these suggestions relate to the yin, shadow, or forgotten side, of life—dreams, night, sleep, emptiness, space, creativity, visions etc. My contention is that the less space there is for these yin parts of life in our world, the more we will experience yang issues like anxiety. May we all find a way to right the balance between these two living forces.

two key themes

There are two key themes that I’ve observed come into play with anxiety:

agency: whether you can do anything to change the situation; how helpless or empowered you feel. relates more to your outer circumstances.

capacity: whether you can handle the situation and your emotions about it; how overwhelmed or capable you feel. relates more to your inner response.

A lack of either one of these can trigger anxiety, but when both are absent, it’s likely to be worse. Because life is full of circumstances we can’t control, much of the time all we can do is increase our capacity to handle those circumstances. Ironically, even when we can do something about a situation, a response that comes out of anxiety or fear is unlikely to be ideal, as it reinforces the pattern at play rather than changing it. This is why it’s so important to shift out of the anxious state and make decisions from a state of relaxation and safety whenever possible. The latter states are when we are able to think creatively about problems and receive solutions from our intuitive or deeper self, as well as when we are more receptive to support and help from the outside world.

→ detox from stimulation

Agency and capacity are strengthened in response to challenge, and in the presence of sufficient support and relaxation. The latter are necessary conditions; without them you may try harder but you don’t actually grow. The downtime after stress is when you are strengthened, just like muscles are built during recovery, after exertion.

When you are anxious, you need to consciously detach from stimulation, especially of the digital kind. The more that is going into your system, the less you can actually process and parse, and the more fragmented you become. Even if you have the capacity to handle a situation, overstimulation will overwhelm you so that you can’t access that capacity. Over time, your sense of your own capacity declines until you are stuck in a negative spiral of being able to handle less and less while being confronted with (what feels like) more and more.

Another way to think about this is that you need to restructure your own boundaries more carefully. Sometimes we feel ashamed of doing this, as if we are running away from the world; on the flip side, some people abuse this idea by blaming others for their own overwhelm. What I am suggesting is to take ownership and be honest about what you can handle, and then to retreat from what is too much while you recover from your stresses and build up your reserves. Life is always a little bit more (and sometimes a lot more) than what we want or need, because we are here to grow.

I want to emphasize that you really don’t need much stimulation to be content and live well. Areas that most people could afford to downsize include:

news media and analysis

number of books, podcasts, movies and TV shows consumed (quality > quantity)

As much as I love entertainment, I take issue with the overabundance and easy availability of it.

inefficient forms of communication like email chains and WhatsApp groups

time spent on social media

exposure to advertising and/or propaganda

social events attended out of obligation or pressure rather than desire

I highlight these because they are all ‘extras’ or optional activities that we choose to spend time on, in contrast to other parts of life that we have no choice but to deal with like difficult bosses, relationship challenges, sickness, bereavement, family problems, financial stress, relocation etc.

I am not suggesting you eliminate the listed things entirely from your life, though you could if you wanted to. I simply invite you to reflect on how much of your time and energy they’re really worth, and make any appropriate changes.

Many of the listed activities are almost guaranteed to leave you feeling worse (with the exception of books, TV, podcasts and maybe social media, if chosen and engaged with consciously). But we continue to do them because we are conditioned to believe that they are necessary, or simply out of habit. The productivity mindset—and its attendant fear of missing out (FOMO)—has taken over everything, even leisure. We need to remember that time spent not doing anything is not wasted time. We do not have to fill every waking moment of life with activity, and we do not need to stimulate mind and senses 24/7 (or even 16/7).

It takes deliberate intention to step away from the prevailing mindset, and to remember how we spent our time before it came along: resting, daydreaming, going outdoors for some fresh air, playing, pottering around the house, taking a stroll, waiting around, people-watching, or simply having pockets of unstructured time without anything to do.

These windows of empty time are when your nervous system starts to unwind and defrag, and you learn the art of just being, without making any demands on yourself. Just a few minutes in that state every day can be enough to start to find your way out of agitation and anxiety.

outer change

I mentioned in Part I that anxiety is a natural response to unpredictable circumstances. Another word for such circumstances is impermanence, which, according to Eastern philosophy, is a defining feature of life.

When we are faced with change in the outer world, particularly overwhelming or extremely rapid changes, it is natural to feel jarred and unsteady. In my case, when I moved to a new country, I needed time and space to establish a new base of support, so that I would feel stable enough to venture out, explore and have new experiences. That base included a secure living situation; familiarity with my neighbourhood and the city; a balanced work-life routine; healthy rhythms of sleeping, eating and moving; and a connection to friends, family and community. These are all indispensible for human flourishing. Sometimes we can do without one or two of them for limited periods of time—but not too many, and not for too long.

The teaching of impermanence comes in to help us make sense of why and how things change; but it is not an excuse to justify living haphazardly. Impermanence is about accepting that there are things beyond your, and my, control. Living in a changing world requires creating your own islands of stability and safety, so that you can face the instability around you with equanimity.

It sounds obvious, but when you are feeling anxious, what you require is not more awareness of impermanence, but rather stabilising structures and routines. Note that anxiety naturally brings forth an instinct to grasp and solidify, to hang on for dear life.1 This is how your fear tries to manage the situation, and it’s not what I’m advising. What you need is to dissolve into the instability and re-create a new form out of it. Or to zoom out of the current chaos and see its larger rhythm and pattern, so that you can find your place in the cycle again.

This is difficult to do on your own, and usually you’ll only realise you’ve done it once you’re out of the anxiety. But you can help yourself along by (1) accepting the impermanence around you as a kind of background, inescapable reality, and (2) consciously re-orienting towards stability wherever you find it: the literal stability of the ground, predictable daily routines, supportive people, healthy habits etc.

time

One of the keys to embracing impermanence is a felt awareness of cyclical time. Cycles, by their nature, are predictable, but within each cycle nests the unpredictability of change. The flow of time is constant, without beginning or end—but as it flows, everything changes.

Linear time, with its goal-oriented and productivity-maximising emphasis, fosters anxiety. It assumes a mindset of scarcity, of limited time, as in the phrase ‘you only live once’, which can be both empowering and frightening. This is one reason people get obsessed with filling their time, because once you’re in linear mode, time’s always running out. Anxiety itself creates a feedback loop that keeps you stuck in speediness: you’re operating at the edge, always slightly faster than necessary.

Cyclical time acknowledges that everything moves at its own rhythm, both within you and outside you. There is no one set speed, and faster is not better, because there is no end to aim for. A cyclical awareness of time makes space for the natural birth-death rhythm of every part of life. We experience this already in the rhythm of day and night, in the lunar and menstrual cycles, in the seasons, and in the phases of our life. We just need to let it in, and let it inform the way we live.

→ rhythm and routine

We may not realise it, but our daily habits often contribute to and increase anxiety. This is because much of modern society was not created with human flourishing in mind, but rather for reasons of expediency or centralised convenience. We are also out of touch with (or even dismissive of) traditional practices that served to anchor us to each other, and to time and place. Thankfully many people are now recognising the value of the way we used to do things and returning to a more naturally-oriented lifestyle.

1. the circadian rhythm

One of the main ways you can do this is to consciously cooperate with biological and natural rhythms, like the rising and setting of the sun (aka. your circadian rhythm). Re-align your day with solar day and night, and let the predictability of the solar rhythm become a container for your daily life.

In urban and modern spaces, it is awareness of night that’s lacking; we artifically extend our daytime as long as we can, sometimes even through the whole night. The night half of the self—which includes the magic of sleep, dreams, rest and repair, and doing nothing—is undervalued or forgotten. To reawaken this part of your self, start by turning down the lights at sunset. Enjoy the evening hours in low light, and see what you feel like when there isn’t as much visual stimulation.

You may notice changes in your mood and energy level, as well as variation in your desire to engage in certain activities, because light is a natural stimulant for humans. Unlike other animals, we are circadian beings, meant to live by the light. This is why different wavelengths of light have an impact on us—think of the difference between candlelight, firelight, sunlight, so-called ‘mood lighting’, fluorescent lighting and neon lighting. Coming back to natural rhythms doesn’t mean that we deny artificial and electronic sources of light—but it means we use them in a way that supports rather than undermines our well-being.

2. the ultradian rhythm

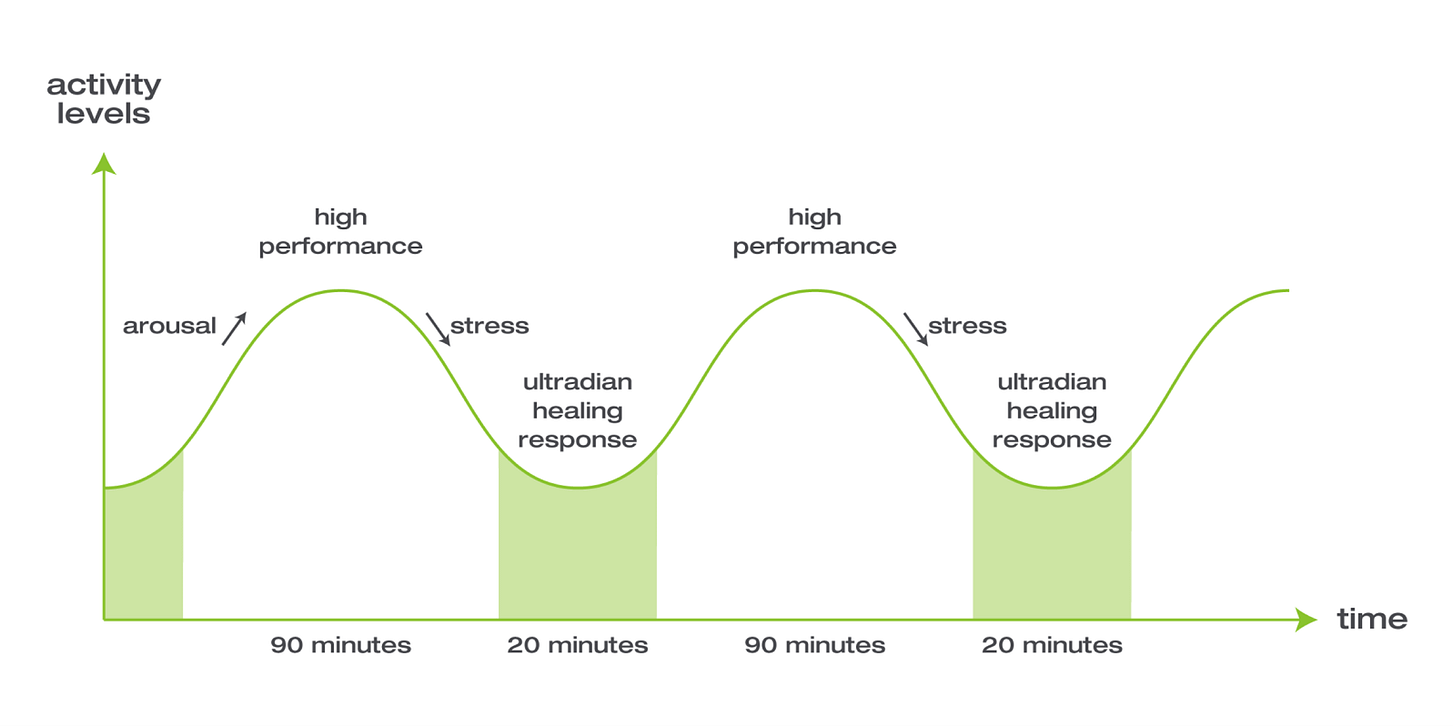

You can also choose to consciously cooperate with other natural rhythms, like your ultradian rhythm. Ultradian means ‘shorter than a day’ and refers to the way brain activity rises and falls predictably in waves throughout the day and night. During the day, every 90 minutes to 2 hours we go through a 20-minute healing phase, when our energy is a naturally a little lower and our brain enters ‘processing’ mode to integrate whatever’s been happening up to then.

In the yoga tradition, each 90-minute wave is thought to be dominated by activity in one brain hemisphere (right or left). During this period, energy flows more strongly through one of the two side channels (ida or pingala), and breath flows through one of the nostrils more than the other. In contrast, the 20-minute intermediate phase is when the central channel sushumna is activated, breath flows through both nostrils evenly, and the brain is engaging both hemispheres simultaneously. Then in the next wave, we switch over to the other hemisphere, channel and nostril, and so on throughout the day and night.

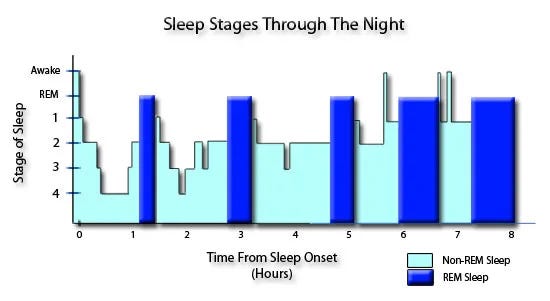

In sleep, ultradian healing phases are when we dream, aka. REM sleep. REM sleep happens every 90 minutes and builds up from shorter (5 mins) to longer (30 mins) over the course of the night. It feels like we dream all at one go, or continuously throughout the night, or not at all, but dreams and sleep happen in waves.

Tuning into your ultradian rhythm is an easy and powerful way to improve your energy, mood and focus throughout the day. Most research and writing about the ultradian rhythm actually emphasises productivity gains. However, its deeper power lies in teaching us how to rest naturally and effortlessly, and in deconditioning us from overriding our physical needs and impulses using willpower or stimulants.

The quickest way to get started with this is to structure your work in blocks of 90 minutes to 2 hours at a time, taking breaks of 5-20 minutes in between.2 Ideally you would try to align with your actual energy level peaks and troughs, rather than time-blocking arbitrarily by clock time, but do what you can.

The next step is to rest deeply (aka. NSDR or non-sleep deep rest) during one ultradian healing phase every day, usually sometime in the afternoon. Many people feel a natural slump at this time, but instead of reaching for coffee or powering through it, take 15 minutes off to ride the wave of your tiredness down and then back up again. Ways to rest deeply include lying down, taking a nap, meditation, breathwork, yoga nidra, hypnosis, stretching or very gentle movement like yoga or tai chi etc.

When we consistently override our body and brain’s natural energy patterns, we get stuck in high arousal and can’t come back down into rest again even when we need to. Cooperating with your natural rhythms is one way to get body and nervous system flowing smoothly between mobilisation and relaxation—a major step and a crucial microskill in reducing anxiety.

3. infradian rhythms

The prior two rhythms (circadian and ultradian) are the most important to harmonise when working with anxiety. However, if you prefer, or once you have those two sorted, you can also work with larger or longer rhythms such as: the lunar and/or menstrual rhythm, seasonal rhythms and even planetary (astrological) rhythms. These all come under the umbrella category of infradian (‘longer than a day’) rhythms.

The lunar and menstrual rhythm is particularly worth exploring if you are a woman, as your anxiety may coincide with phases of your cycle corresponding to the hormonal changes you are undergoing. Sometimes just knowing when you’re likely to be a little more tense or agitated is enough to put things into perspective and make them seem less overwhelming. Cycle awareness also has the power to lead to better choices and more effective self-care during your vulnerable times.

inner change

Anxiety also arises when we are called to evolve and mature. It is the protective layer over deeper feelings, which, when encountered, prompt us to re-evaluate ourselves, our choices, the life we’re living, the patterns we’re playing out. We become aware of the distance between what we are and what we could be—but before we can do anything about it, we have to first confront our anxiety at letting go of the familiar contours of our present self. In this case, the trigger is not simply an external circumstance (though it still can be), but a call-and-response between inner intuition and its outer echo.

While I no longer experience debilitating anxiety like I had when moving to Barcelona, this kind of anxiety still arises on occasion. It’s there when I am about to do something big that I’ve never done before—like when I taught my first corporate workshop. Or when I’m about to publish a piece of writing on a topic that’s new to me, or that’s been a stretch to create. When I have decided to let something go that I depend upon, without knowing what’s going to replace it. And of course, it’s right there with the vulnerability of heartfelt relationships. This kind of anxiety is part and parcel of life, built-in to us because we change, and everything changes.

We do one thing or another; we stay the same or we change.

Congratulations if you have changed.—Mary Oliver, To Begin With, The Sweet Grass

→ dreams and visions

I believe that the best way to work through inner anxiety is to turn to depth practices like dreamwork and visionary experience. These practices exist in the liminal zone between what is and what could be, so they come from the same place as inner anxiety.3 Working with them is a way of following the maze to its center—where you find the core message under your anxiety—and then back out to its exit as you manifest your changed identity in the world.

In dreams and visions, everything blurs together and not much makes sense: but that confusion and chaos is what births new possibilities and creative ideas. It can be difficult to let go of anxious mind’s desire to solidify and delineate everything, but it is possible to just be with the hazy, uncertain flow of images and thoughts and let them coaslesce into understanding on their own. Much of what you dream up may be incidental or ultimately discarded, but it is the process of opening up to your own mind that allows all possibilities to be explored and the right one to be discovered.

A side benefit of engaging in such practices is that they radically strengthen your trust in your deeper self and in the universe. You begin to feel there is a pattern underlying it all, even if you are only catching the tiniest glimpses of it. And you know that wise guidance is available to you, if only you can ask and listen for it.

Start by keeping a dream journal, where you record any dreams you remember. I may have recommended these before, but this book and this podcast are fantastic resources on dreamwork.

If you prefer to work with visions, it’s best to seek guidance from a practitioner who will be able to create the right kind of container and experience for you to slip into, and guide you to discern and integrate properly afterwards. Note that I am not talking about visualization, which is where you create mental images and attempt to actualize them in reality. Visionary experience is about surrender and receiving guidance, not about control or manipulation.

Conclusion

I hope that this post gave you fresh ideas and inspiration to work with anxiety. Although I knew it was on the rise, writing this series opened my eyes to just how many people are suffering, often silently and with little hope of change. So if you found any of my words helpful, please consider sharing them with others. You never know what could change someone’s experience.

I welcome comments, questions and feedback on this post or the series as a whole. Also feel free to share any requests on topics that you would like me to write about.

Next up, I plan to write a few standalone posts to take a break from this long series. I’ve just started working on a piece about sacrifice, but in truth, I never know what’s going to emerge. Please subscribe to stay in touch, and upgrade to paid if you appreciate what I’m doing here:

This is reflected somatically in the physical tension that characterises an anxious posture. Body is locked in a pattern of holding, but can’t actually find stability in whatever it’s trying to hold on to, which perpetuates more holding, and so on. This is also why it can sometimes generate more anxiety when you try to release tension—because you’re so used to holding on, despite the discomfort and pain it causes.

When I first found out about this, I was amazed because it reminded me of the structure of my days at school. Lessons were always 45-90 minutes, and in between we had either short breaks (5 mins) to move between classrooms, or longer breaks (20 mins-1hr) for snacks and meals. I’m not sure if it was a happy accident or whether my school was aware of what they were doing. Note that the ultradian cycle for children and teens is shorter than for adults, ie. they need more frequent breaks, and more of their breaks should involve movement.

It’s not a coincidence that dreams/REM sleep and the ultradian healing phase are night and day equivalents—or we could say, the yin and yang—of each other.