In the summer of 2023, I published a 5-part series called An Embodied Guide to Anxiety (starts here). It was inspired by conversations and encounters with people who were suffering from anxiety and wanting my help with it, as well as my own personal experience with severe anxiety during a relocation in my late teens.

Over the past two years I’ve been grappling with another very common life experience: grief, or heartbreak. And somehow, in the way that all things come full circle, many of my clients and friends have also been going through similar challenges and reflecting on them with me. So I decided to create another series, walking us all through a somatically-informed approach to grief, loss and heartbreak.

One of my teachers used to say, we’re all either in the middle of a disaster, or in between disasters. In other words, loss is universal, and we will all enter the portal of grief at one point or another in our lives. This series is meant for those who are in the midst of a disaster, as well as those who may be doing OK for now, but are looking for ways to support grieving friends, relatives and partners.

breakdown

Part I will be about orienting to grief from a macro perspective: What is its role and meaning in life? What is the healthiest way to look at it? This first post is about context, introducing you to a way of regarding grief that places it properly, where it belongs, in the cycle of life and death.

In Part II, we’ll move on to Perspectives, or a variety of somatic lenses through which you could recognize the process and state of grief. This post provides the foundation of awareness, which is always the first step in creating transformation. The information I share here will help you understand yourself and others in your life who are going through heartbreak, and how it is affecting you/them on a visceral, embodied level. What is actually happening inside you as you feel sadness and mourn the loss of something precious? What happens to your perceptions, your physicality and your cognition as you are initiated into the process of dissolution and rebirth that marks every loss?

In Part III, we will build on this understanding with tools and approaches you can take to either support yourself within your grieving process, or gently nudge yourself out of it, and back towards life again. These will also be useful as ideas to help you support others in your life who may be grieving or in the midst of heartbreak.

It is my hope that these posts touch the part of you that is ready and willing to heal, but just needs a little reminder and some encouragement in the right direction. I also hope to give you, through my words, the quality of self-compassion that is so crucial in times of grief. One of the essential skills in working with grief is gentleness, or what we could more technically call titration: the ability to do just enough, and no more, than we need. (More on this in the section on the nervous system.)

Please take this in at your own pace, in your own way, honouring where you are now. As always, let me know what strikes you, if anything is unclear, or if you need more support. And feel free to share this with others if you feel they would benefit.

What is grief?: a few perspectives

grief is love, inverted

Grief and heartbreak are natural responses to loss of any kind. We sometimes confine the word grief to refer to the loss of another human, but we can equally and deeply mourn the loss of a job, a phase in life, a relationship, a place or a part of ourselves. I often use the word heartbreak in these contexts because it is so immediate and direct to the actual experience of grieving.

One thing I find helpful to remember is that grief arises out of care, or love. We do not mourn things we don’t care about; conversely, we only feel heartbroken about the things that truly mattered to us. In this way our grief is a barometer and a symbol of the depth of our feeling about whatever we have lost.

It is futile to try to convince ourselves that what we lost didn’t matter, or was meant to go anyway. Often these are top-down responses to try to will away the pain—but grief has its own language and will not usually respond to such mental gymnastics. In this way, there is an undeniable clarity and truth-telling to grief, for it shows us exactly where we stand in relation to others and to our past and present selves.

Grief may be tied up with other feelings, such as anger, betrayal, helplessness, shame… but at its core it is a form of love. The difficulty is usually that the object of our love has changed, or disappeared (hence the heartbreak). But the love itself is still there, and it is the force that guides us out of grief and towards healing.

a mirror to reality

Loss is an immediate and undeniable confrontation with the reality of impermanence, or cyclicity. All things begin and end, or are born and die, or come into our lives and then go away. In our naïveté, we forget this truth, and so the world conspires to remind us of it over and over again: in the rhythm of day and night, in the wax and wane of the moon, in the turning of the seasons, in the cyclicity of our bodies, and of course, in times of grief, the winter of the heart and soul.

The first time I ever lost someone I cared about, one of my mentors told me something I remember to this day. She said: those who have lost see more clearly than others, because they are in touch with a dimension of reality that the rest of us have forgotten, or that we try to deny.1

Grief is therefore an invitation to a different kind of perception, a visceral way of knowing our own vulnerabilities that temporarily sets us apart from the ordinary world and everyday consciousness. It is an experience that shatters our illusions and complacency about being here and being alive. Old routines and habits fall apart, stop making sense, or fail to exert their usual gravity on us. In an encounter with grief, we lose touch with the solid ground of ordinary perception; everything is now tenuous, vulnerable, and achingly precious for it.

As a meditator, there are few things more valuable than those that alter your state and bring you closer to reality. Therefore, if you choose to claim it, grief becomes a gateway to clarity, to a truer and more accurate perception of the way things are, and therefore to a way of living that is more aligned with what is.

Grief hurts us all the more when we are unprepared, and yet once it hits there can be a sense that all our preparation has gone out the window. We are never really ready; and the reality of loss is never the same as what we imagine it to be. The best we can do in the moment is accept the call of our grief: to rejoin the cycle of life and death, dissolution and recreation, from which we had been estranged.

initiation and rebirth

There is a shadowy quality to the experience of grief and heartbreak; a feeling that we are alone, in the dark, in a place we don’t know how to navigate. Partly this comes from the way that our bodies and nervous systems shut down or close us off from the world to conserve our energy (more on this in Part II).

But there is a deeper truth to both the darkness and the not-knowing. Part of grief is accepting that we cannot be the same self through our heartbreak. Processing it means dying to an older self and birthing a new one, a self that we don’t yet recognize and cannot feel the contours of. This is what it means to be initiated, in the traditional sense of the word.

Initiations, by necessity, happen in the absence of our habitual ways of seeing the world. We lose sight of the things that used to light us up and draw us onward, because grief forces us to find a different way of orienting to life and reality. And in order to find that way, we have to go down into the darkness, and wait for the light of a new dawn to emerge and guide us once more.

When we allow ourselves to grieve and be transformed by our grief, we are—essentially and paradoxically—reaffirming our participation in life again. Change is a mark of life; only what is alive can change or be changed. In this way, accepting a confrontation with death or dissolution restores us to the flow of life.

closing supports

There are two powerful forms of support that I offer to myself and to those I know who are going through grief. The first is ritual. In times past, ritual and community were the default response to grief, especially death. Now, many of us either do not know the rituals of our ancestors or feel alienated from them; or we may be grieving things that we don’t know how to ritualize.

The power of a ritual is that it:

creates space for the body to enact change in symbolic and subconscious ways

gives embodied meaning to the internal, invisible transformations that we go through when we lose something

keeps us moving through the cycle of change, so that we don’t get stuck in one place or response

puts us back in touch with the unseen world that is always offering support and guidance to get us through tough times

It is more than worthwhile to consider for yourself how you can ritualize your grief. You may draw from some ancestral tradition, or make up your own—the specifics don’t matter. What does matter is that you create time and space to honour the transition and the loss you have faced, in a way that is meaningful to you. There is an innate wisdom that emerges when you follow the call to ritualize; or perhaps it’s actually the unseen world guiding you via your own intuition. Either way, once you start, you will know what is right to do, when and for how long.2

The second support I offer is creativity. Grief has a way of pulling us out of the flow of life, both outside and inside of us. The life force within us gets dampened or wounded, and we may need much rest and care before it flickers alive again. Taking up a creative project or activity can help reanimate yourself, either once you feel ready, or in parallel with your grieving process. Making something new is a way that your body enacts the process of creation, rather than dissolution.

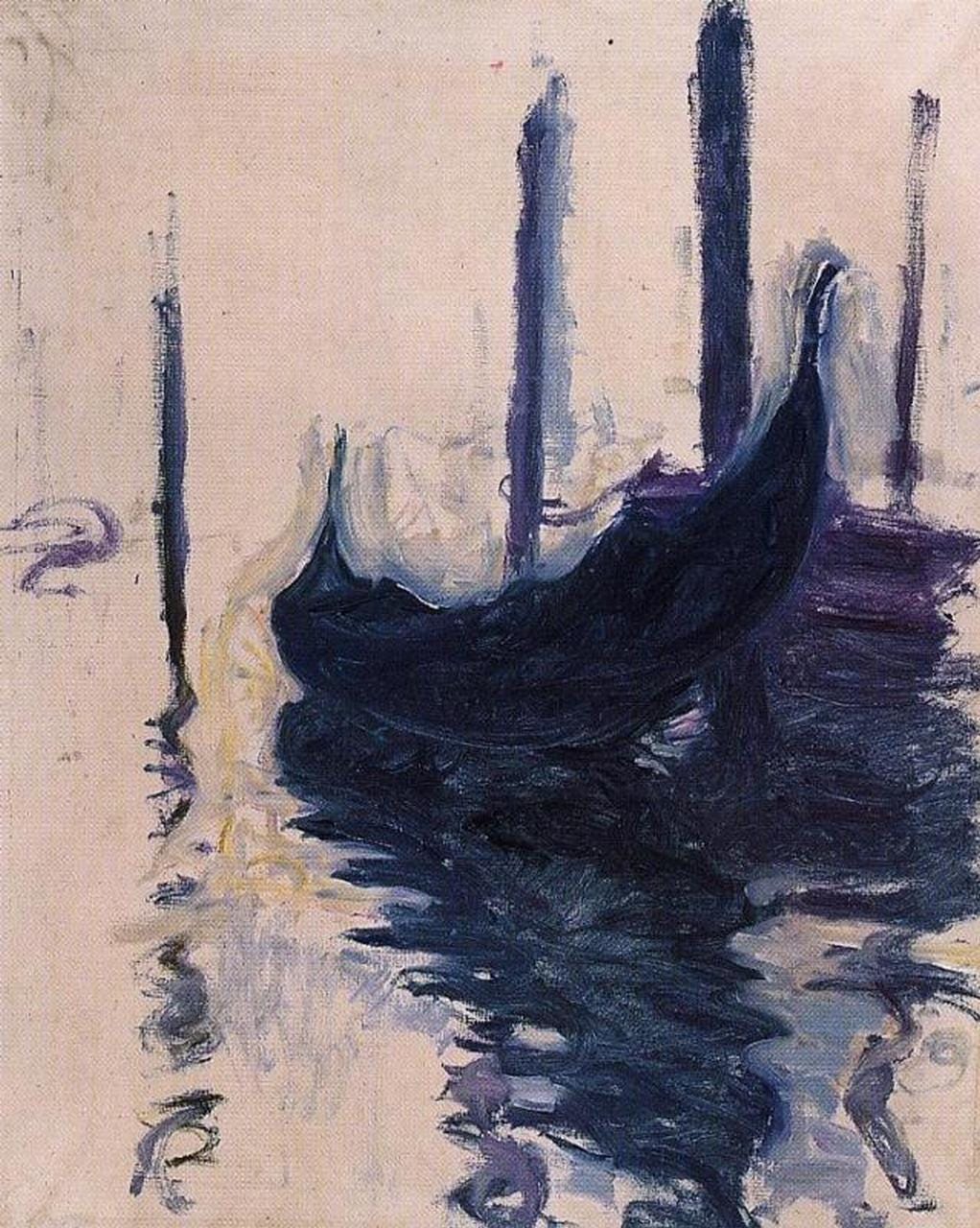

What you create doesn’t matter: it could be a song, a painting, a form of craft, a poem… Whatever it is, emerges from the invisible darkness inside of you, as a spark of new life that you have given birth to. It is a way that you reorient from what you have lost to what you were given, and what you still have, and what you can still have. Creation takes you out of the weight of the past and into the living possibilities of the present and future.

In Part II, we move on to embodied perspectives on grief; or how the body experiences and processes grief.

This also translates to how we regard those around us who are grieving. We can respect and honour their grief, because it places them (temporarily) between the world of the living and the world of the dead, or between the seen and unseen worlds.

If you need inspiration, some of my rituals have included: going to a place that was/is special (like a pilgrimage), listening to a certain kind of music in homage, writing letters and offering them to a fire, moving my body to express my feelings, planting something, creating an altar and making offerings, spending time in prayer/contemplation/meditation…

a delicate topic of which you present good suggestions and an overall format/approach, very important as so much violence and and lack of grieving get normalized via corporate news and mainstream society. An excellent book is Martin Prechtel's "The Smell of Rain on Dust: Grief and Praise" or his talk, audio "Grief and Praise part 1"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6h3JNOCTYc

part2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTMYHP3ZROs&list=PL-zu_tfn8YObHRYP0j3zxoFjOSMFrrJoN&index=2

part3: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jth9D6VtStg&list=PL-zu_tfn8YObHRYP0j3zxoFjOSMFrrJoN&index=3

Thank you for writing so beautifully about grief, I look forward to the series. I love that you suggest ritualising grief - unless we belong to a spiritual tradition or religion, in the western world those 'rituals' can feel very cold and meaningless. We need to reclaim ritual and make it meaningful for ourselves. I'm very impressed with the work of Francis Weller who recognises that many of us are grieving the loss of biodiversity and the natural world, but have no way of naming or properly grieving that. He believes that grief has been too privatised in western society and conducts large grieving circles so that we can come together and transform our pain, allowing us to move from denial and paralysis to regenerating our natural world.